Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Problem of Action meets Habitual Processes

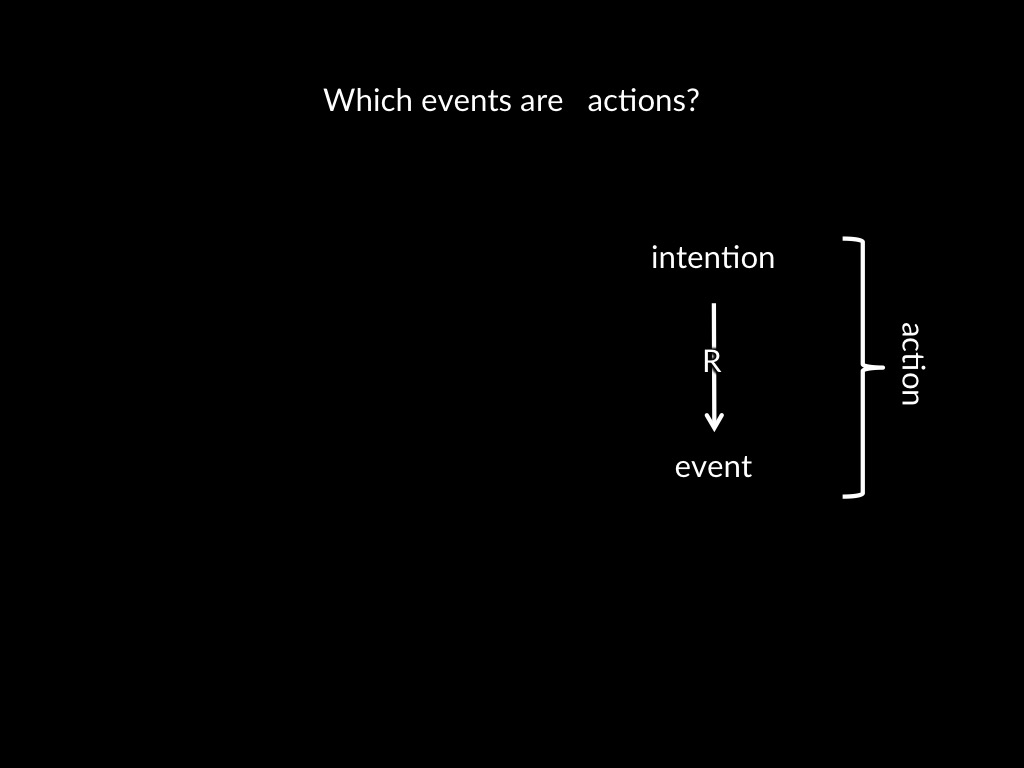

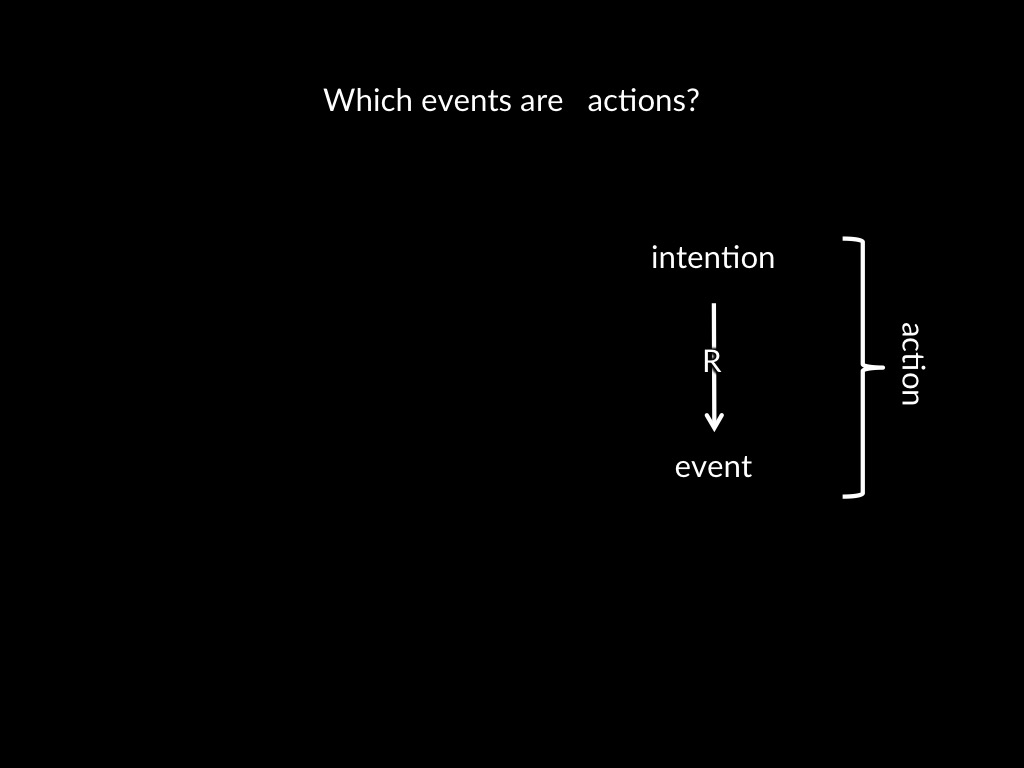

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention; and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

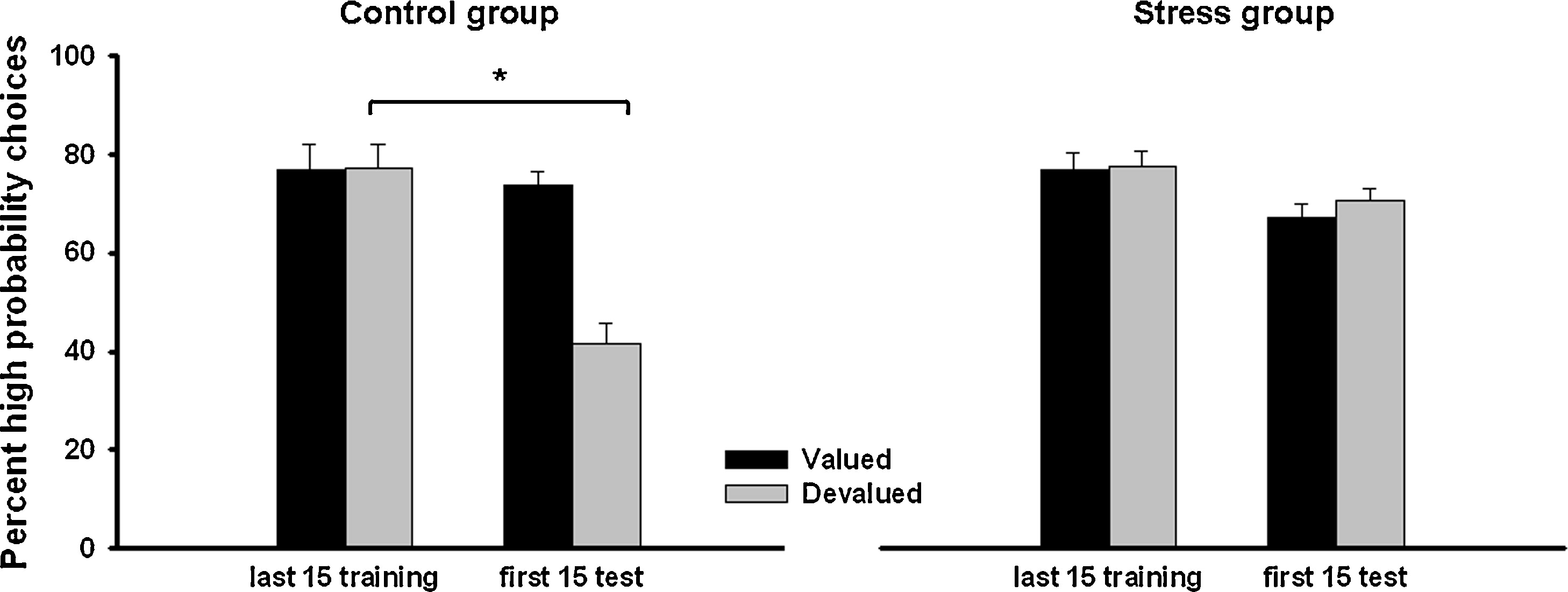

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

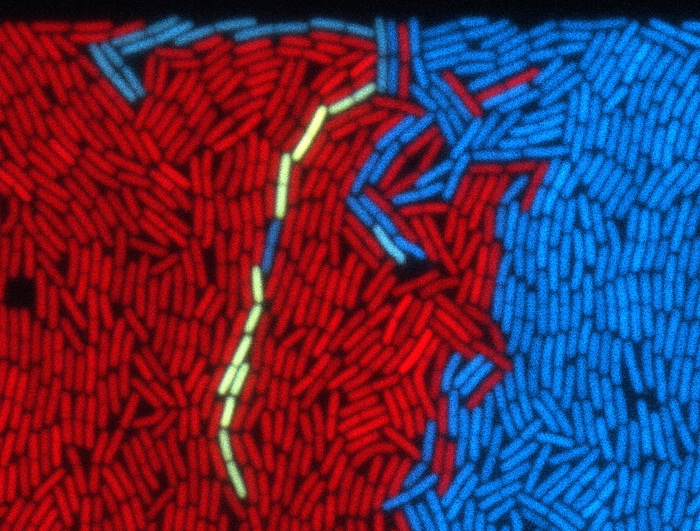

Schwabe & Wolf (2010, p. figure 6)

Sometimes your instrumental actions manifestly run counter to your intentions.

1. Preferences shape intention:

pathological cases aside,

if there are two outcomes

and you prefer one outcome to the other,

and there are no reasons to pursue the other outcome,

then you will not intend an action that brings about the less preferred action.

2. Where habitual processes dominate, you sometimes pursue less preferred outcomes.

Therefore

3. Sometimes your instrumental actions manifestly run counter to your intentions.

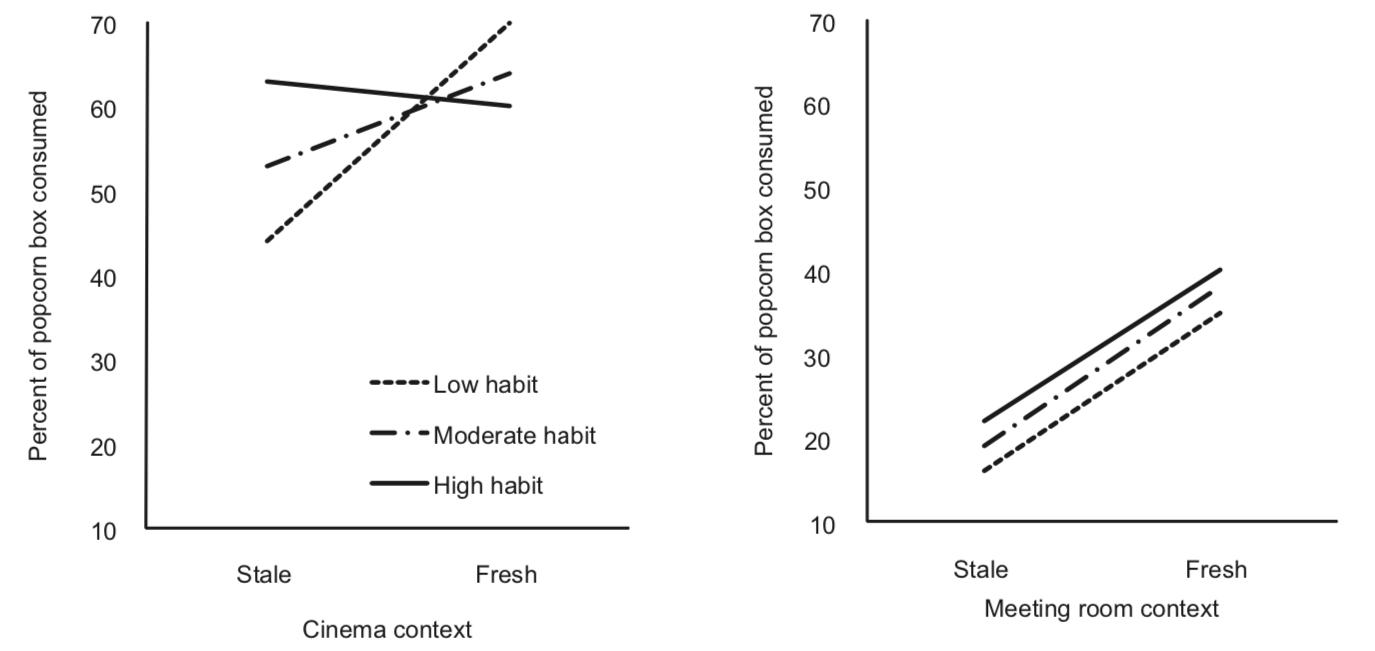

another example—new study (popcorn)

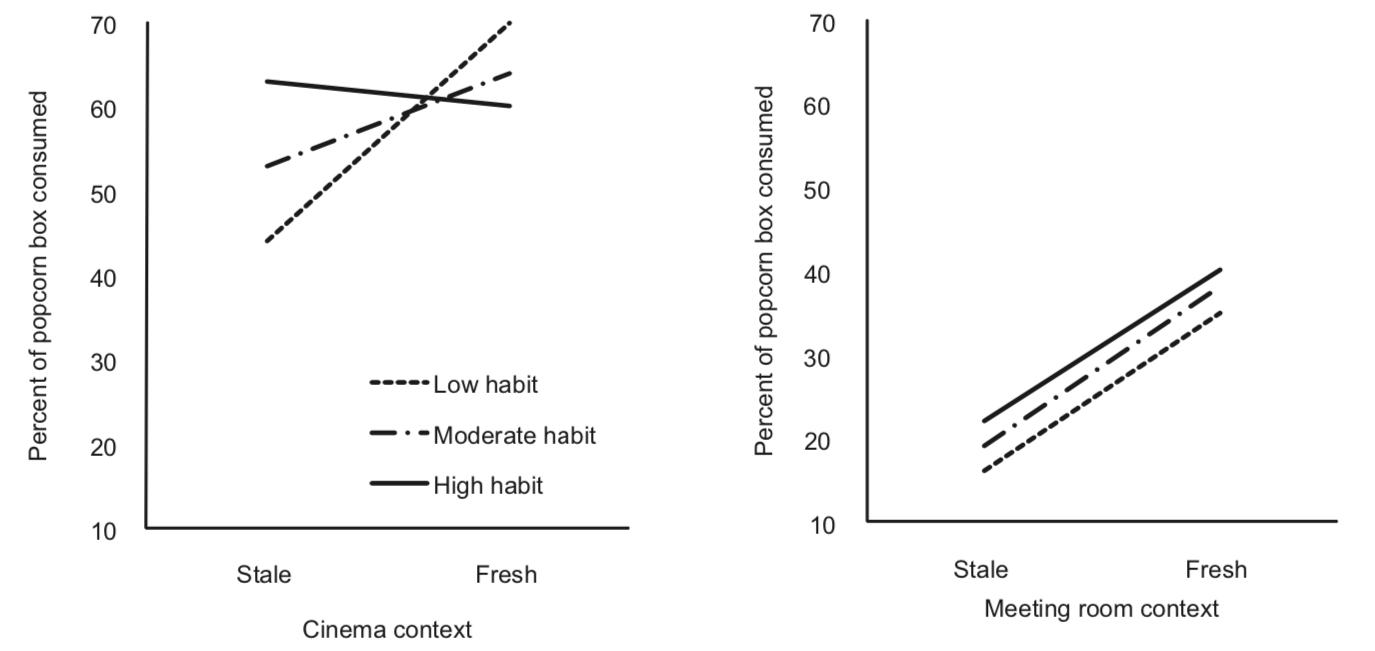

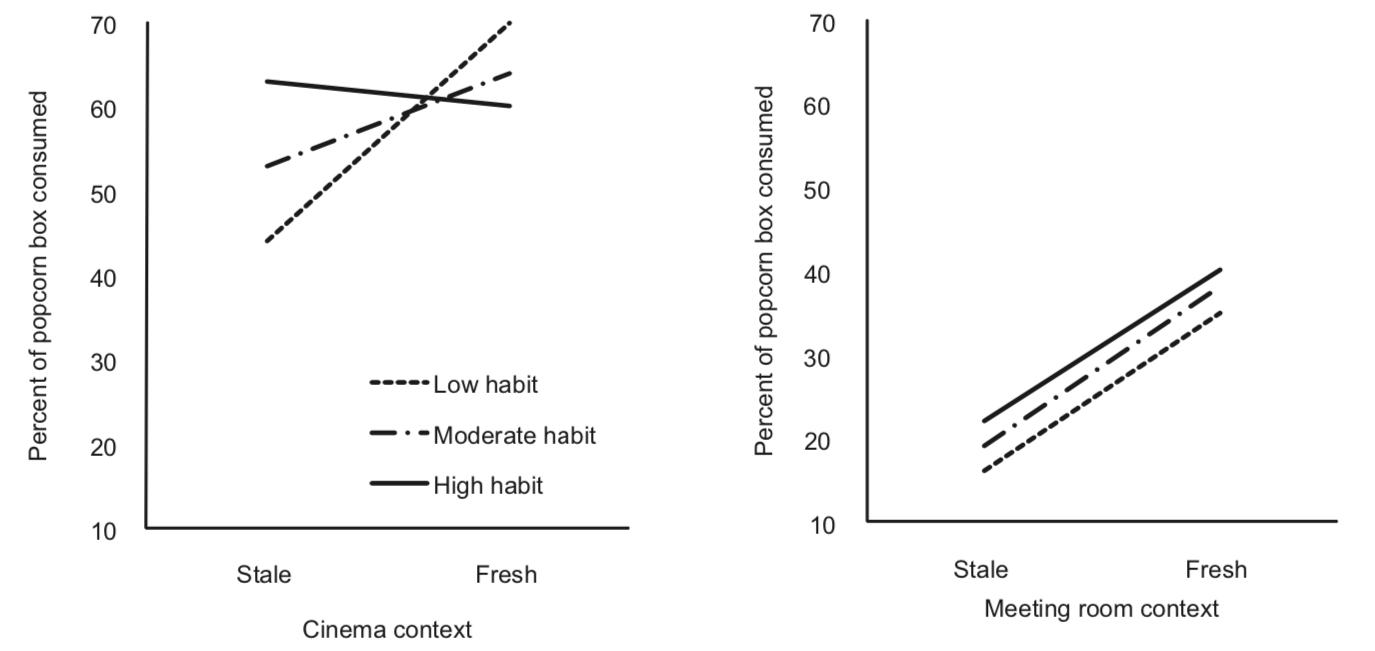

Neal, Wood, Wu, & Kurlander (2011)

Sometimes your instrumental actions manifestly run counter to your intentions.

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

aside: you can also make this argument using AHS

(Della Sala, Marchetti, & Spinnler, 1991)

response 1

insist there’s an intention

‘A man moves his finger, let us say intentionally, thus flicking the switch, causing a light to come on, the room to be illuminated, and a prowler to be alerted.

Some of these things he did intentionally, some not

intention is [...] required only in the sense that the movement must be intentional under some description.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 53)

Neal et al. (2011)

option (i) - the intention to eat the stale popcorn is more common in ‘high habit’ group ... but only in the cinema

‘strong-habit participants experienced the shift in motivation as a function of the food’s freshness. They rated the fresh popcorn as more likable than the stale, and thus they did not value the popcorn more than those with weak habits. [...]

‘Furthermore, tests of whether the habit effects depended on liking for the popcorn or current hunger revealed that these factors did not moderate the effects of habit strength on eating.’

(Neal et al., 2011, p. 1432)

option (ii) - there are other intentions, perhaps intentions to empty the bag, or intentions to grasp and place

option (iii) - intentions are in the background ...

DanielKnoth [2022–23] Conjecture

(a) when the habit was originally formed, there existed some kind of intention and

(b) the habitual process, later on, is still linked to that original intention

[see also Bratman (1984) on ‘motivational potential’]

Neal et al. (2011)

option (i) - the intention to eat the stale popcorn is more common in ‘high habit’ group

option (ii) - there are other intentions, perhaps intentions to empty the bag, or intentions to grasp and place

old: stimulus–action + stimulus → action

new: stimulus–action + stimulus → intention → action

option (iii) - intentions are in the background

response 1

insist there’s an intention

aside: argument structure

evidence -> theory -> objection

vs

evidence -> objection

'->' = 'supports'

response 1

insist there’s an intention

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

response 2

deny instrumental actions are all actions

‘Among the things I did were

get up,

wash,

shave,

go downstairs, and

spill my coffee.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 43)

‘Among the things that happened to me were

being awakened and

stumbling on the edge of the rug.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 43)

eating popcorn

pressing a button to watch a film clip

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

Standard Solution: actions are those events which stand in an appropriate causal relation to an intention.

‘deviant causal chains’ (Davidson, 1980, pp. 78--9)

Minimally, the action should not manifestly run counter to the intention;and neither should whether the action occurs be independent of what the agent intends.

Objection: some instrumental actions manifestly run counter to the agents’ intentions.

Why is this an objection?

How do we know? From persistence following devaluation!

challenge

Discover why people act,

individually and jointly.