Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Minor Puzzle about Habitual Processes

What evidence supports the dual-process theory of instrumental action?

Is this lever pressing primarily a consequence of habitual processes?

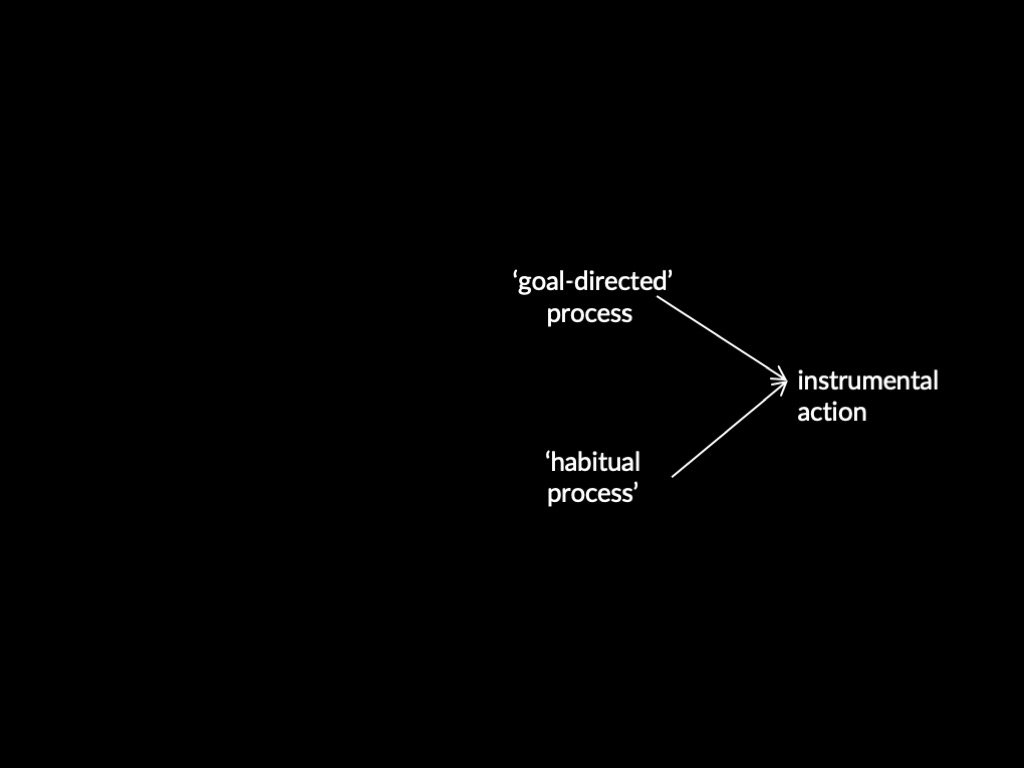

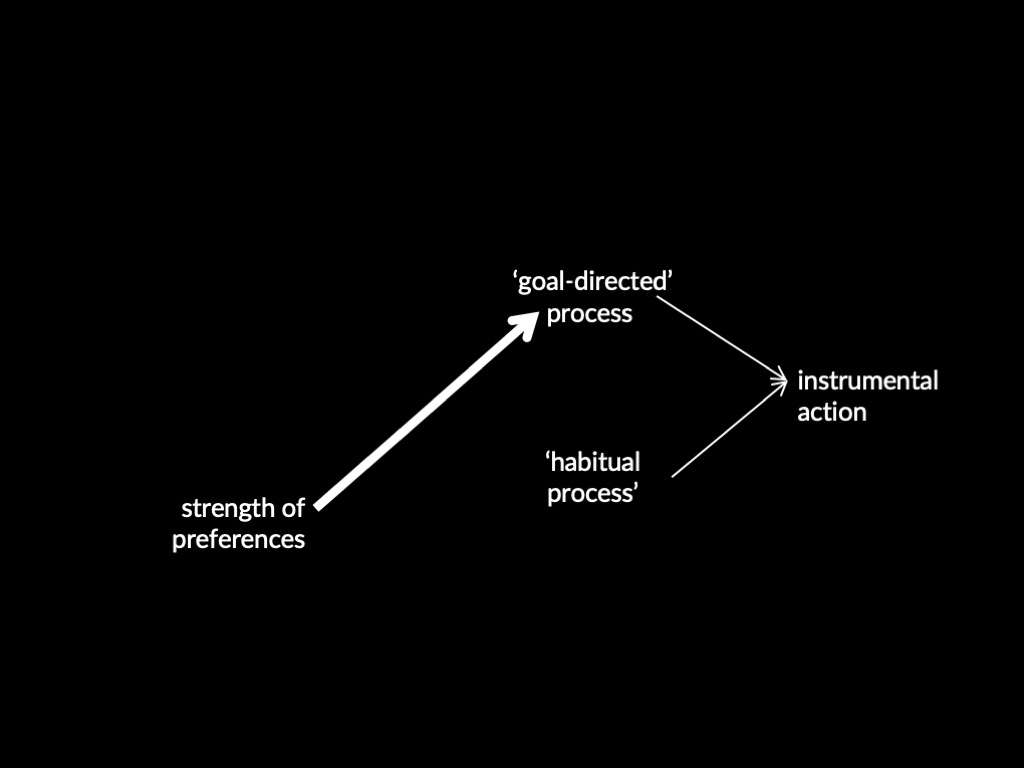

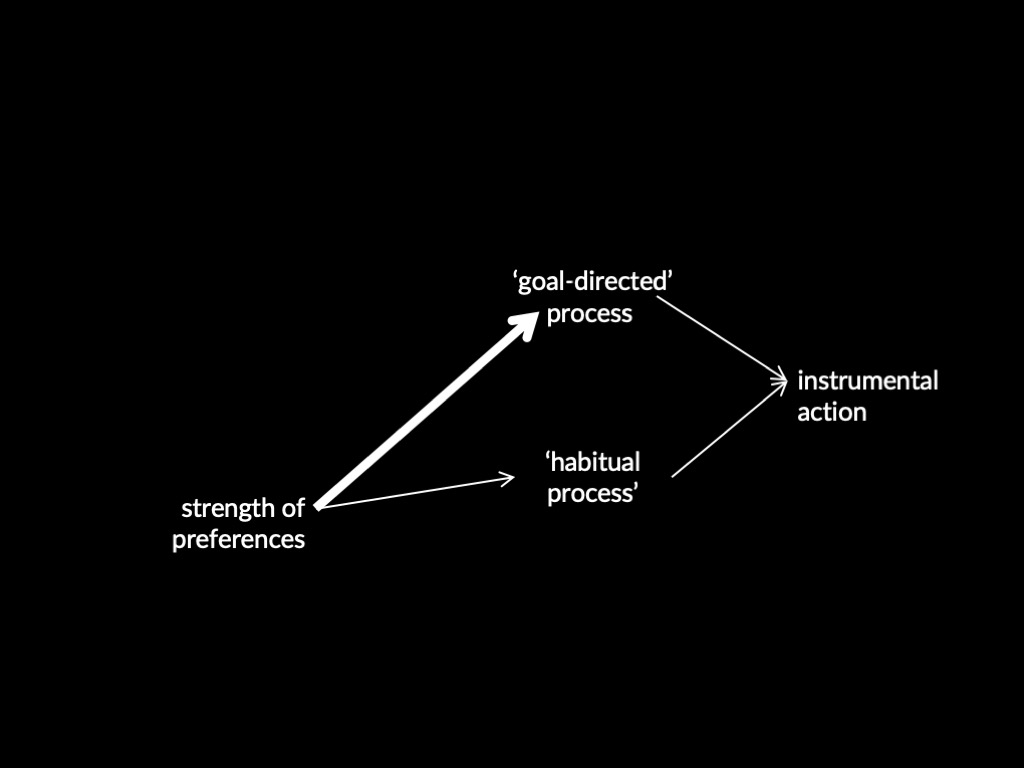

habitual process

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

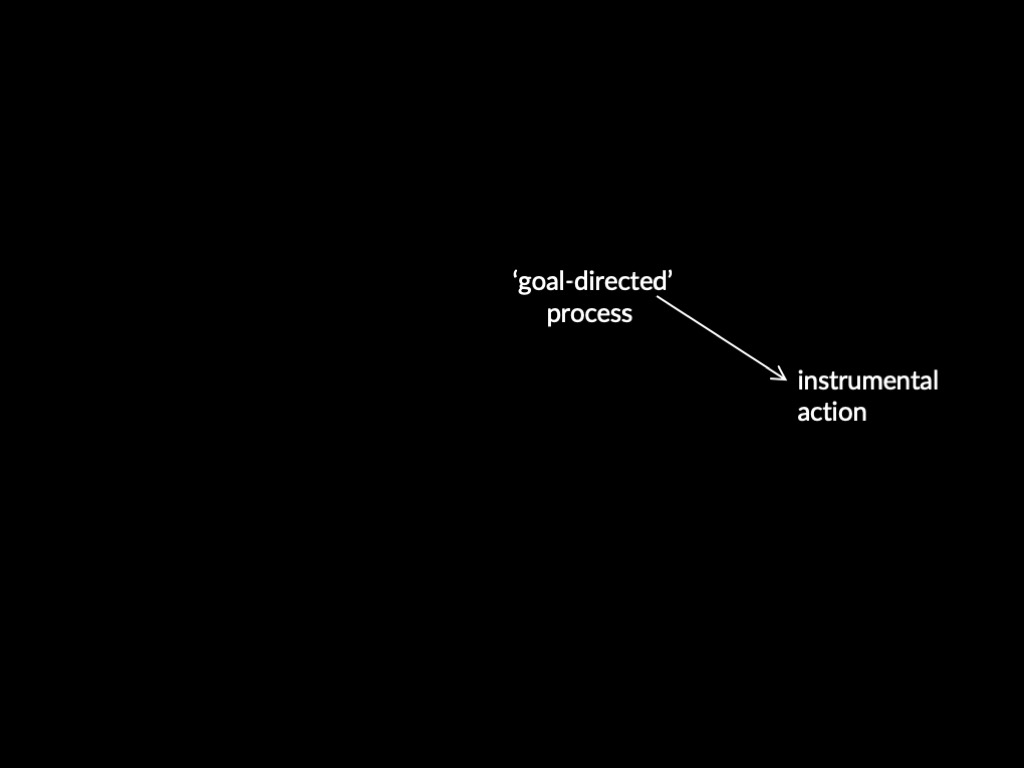

‘goal-directed’ process

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

Problem: different hypotheses, same prediction

Why is taking out your latchkey out on arriving at the door-step of a friend likely to be an action dominated by habitual processes?

Can we use the same principle here?

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

habitual process

Stimulus is the layout of this room.

Rat (=Agent) is rewarded with food

Room-LeverPress (=Stimulus-Action) Link is strengthened due to reward

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur in this room (=Stimulus).

‘goal-directed’ process

Lever pressing (=Action) leads to food (=Outcome).

Thf LeverPress-Food (=Action-Outcome) Link is strong.

Rat (=Agent) has strong positive Preference for food.

Thf LeverPress (=Action) will occur.

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

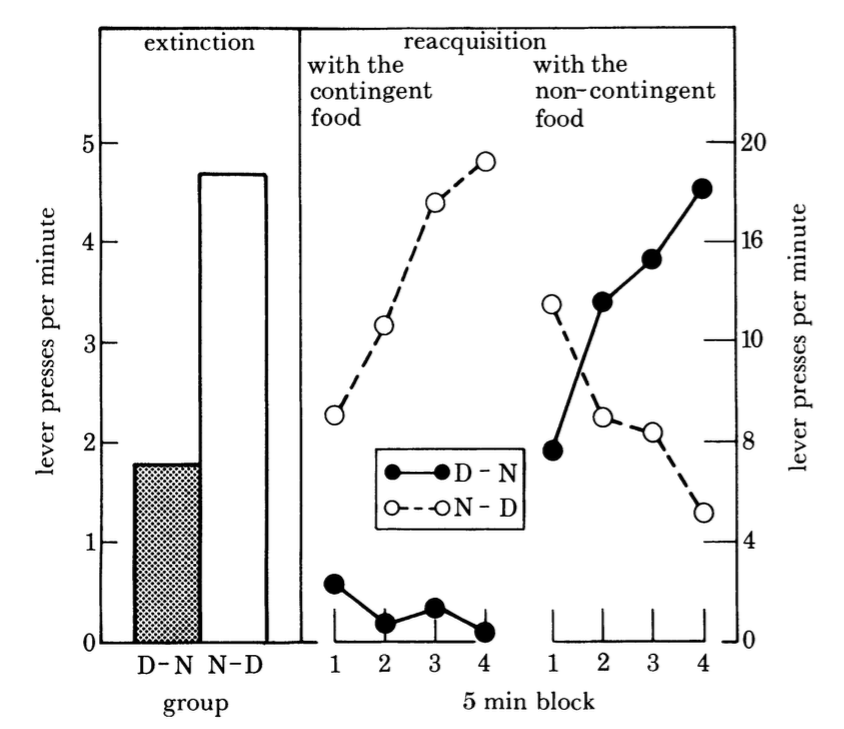

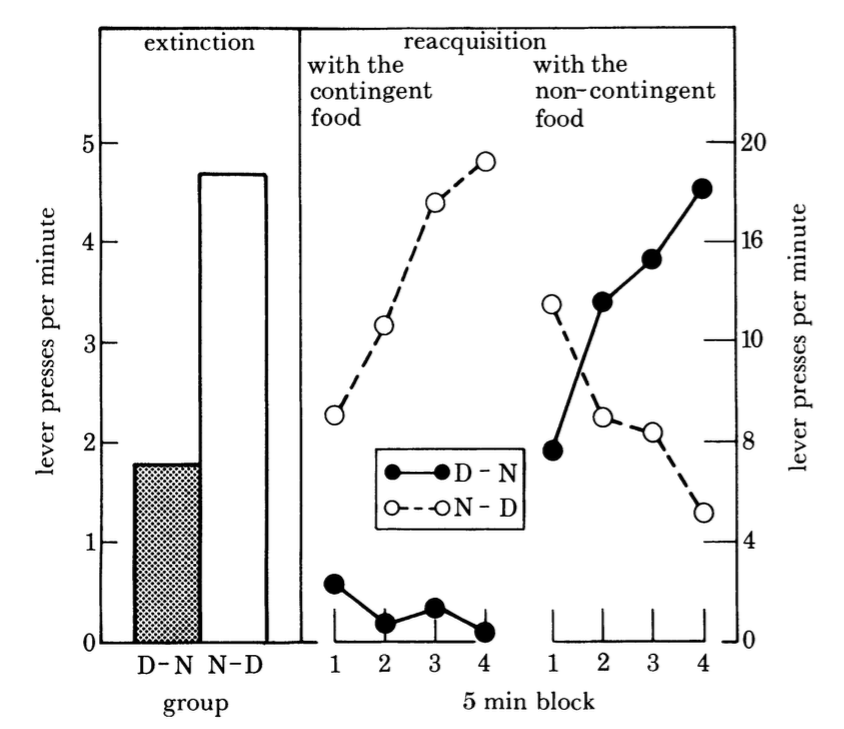

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled by knowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

(Dickinson, 1985, p. 72)

so far ...

1. habitual ≠ habitual

2. We can test whether an action is dominated by habitual or goal-directed processes using devaluation in extinction.

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled byknowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

(Dickinson, 1985, p. 72)

Dickinson, 1985 figure 3

puzzle

If the action is habitual,

why is it influenced by devaulation at all?

If the action is not habitual but controlled by goal-directed processes, why does it still occur after devaluation?

What if we devalue the food in extinction?

‘Goal-directed’ process : it will reduce lever pressing (to none)

Habitual process : it will have no effect on lever pressing

‘the laboratory rat fits the teleological [goal-directed] model; performance of this particular instrumental behaviour really does seem to be controlled byknowledge about the relation between the action and the goal’

Dickinson, 1985 p. 72

‘we did not conclude that all such responding was of this form.

Indeed, we observed some residual responding during the post-re-valuation test that appeared to be impervious to outcome devaluation and therefore autonomous of the current incentive value,

and we speculated that this responding was habitual’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

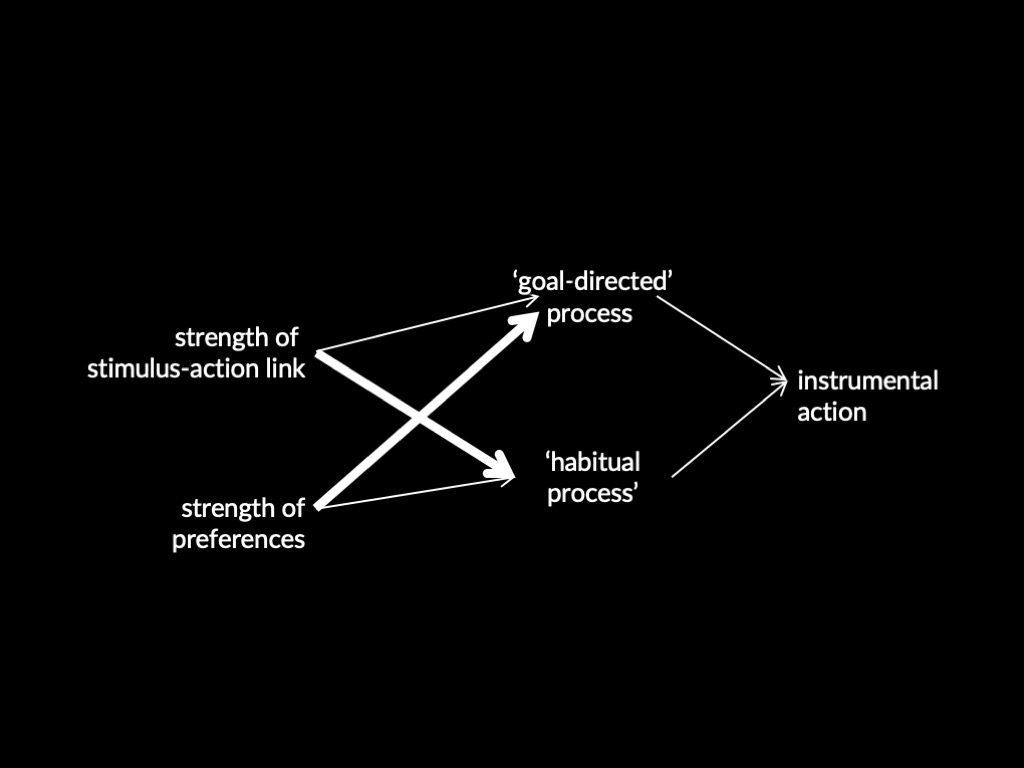

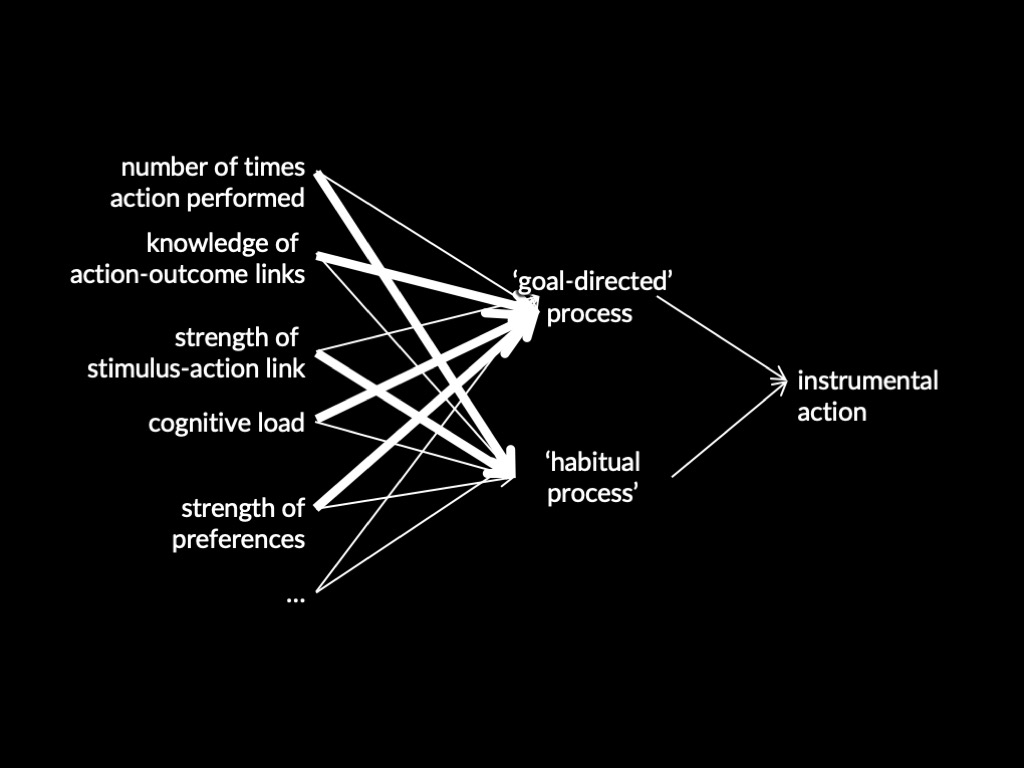

Dual-Process Theory of Action

some instrumental actions are ‘controlled by two dissociable processes: a goal-directed and an habitual process’

Dickinson, 2016 p. 179

Is this lever pressing primarily a consequence of habitual processes?

Probably not most of the time—but it is some of the time.

so far ...

1. habitual ≠ habitual

2. We can test whether an action is dominated by habitual or goal-directed processes using devaluation in extinction.

3. The dual-process theory of instrumental action (habitual and goal-directed processes both influence an instrumental action)