Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Question Session 09

Question

What distinguishes genuine joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

In joint action, each agent intends that

they, the agents, J.

The Simple View

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

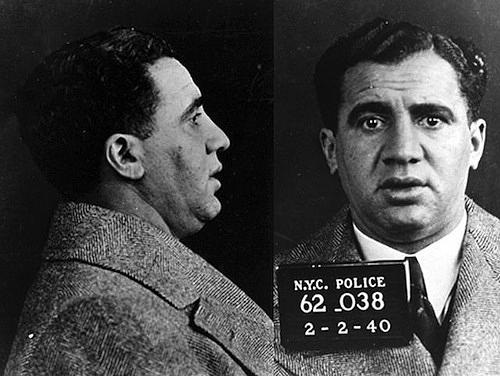

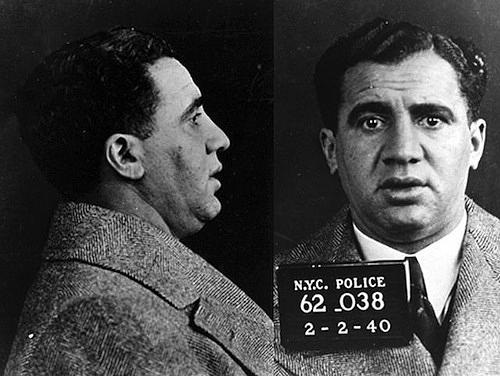

Bratman’s ‘mafia case’

‘each agent does not just intend that the group perform the […] joint action.

‘Rather, each agent intends as well that the group perform this joint action in accordance with subplans (of the intentions in favor of the joint action) that mesh’

(Bratman 1992: 332)

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

We have an unshared intention that we <J1, J2> iff

‘1. (a) I intend that we J1 and (b) you intend that we J2

‘2. I intend that we J1in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

We have a shared intention that we J if

‘1. (a) I intend that we J and (b) you intend that we J

‘2. I intend that we J in accordance with and because of la, lb, and meshing subplans of la and lb; you intend [likewise] …

‘3. 1 and 2 are common knowledge between us’

(Bratman 1993: View 4)

| true? | A&A make use of? | |

| Ayesha intends J1 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Ahmed intends J2 | ✓ | ✓ |

| J1=J2 | ✗ | ✗ |

| true? | B&B make use of? | |

| Beatrice intends J1 | ✓ | ✓ |

| Baldric intends J2 | ✓ | ✓ |

| J1=J2 | ✓ | ✗ |

Joint Action

Parallel but Merely Individual Action

Two people making the cross hit the red square in the ordinary way.

?

Beatrice & Baldric’s making the cross hit the red square

Two sisters cycling together.

Two strangers cycling the same route side-by-side.

Members of a flash mob simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

Onlookers simultaneously open their newspapers noisily.

Beatrice & Baldric’s activity meets Bratman’s conditions.

Beatrice & Baldric are not exercising shared agency.

∴ Bratman’s conditions are not sufficient.

‘The notion of a we-intention [shared intention]

... implies the notion of cooperation’

Searle (1990, p. 95)

Joint commitment is a ‘precondition of the correct ascription’ of acting together ...’

Gilbert (2013, p. 9)

For us to have

a shared intention that we φ

is for us to be jointly committed

to emulate a single body

which

intends to φ.

| Brat-man | Searle | Gil-bert | Blom-berg | Pach-erie | ... | |

Are all joint actions cooperative? | ✗ | ✓ | ✗? | ✗ | ✓? | ... |

Are commitments necessary for joint action? | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ... |

Does acting jointly entail being aware of doing so? | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ... |

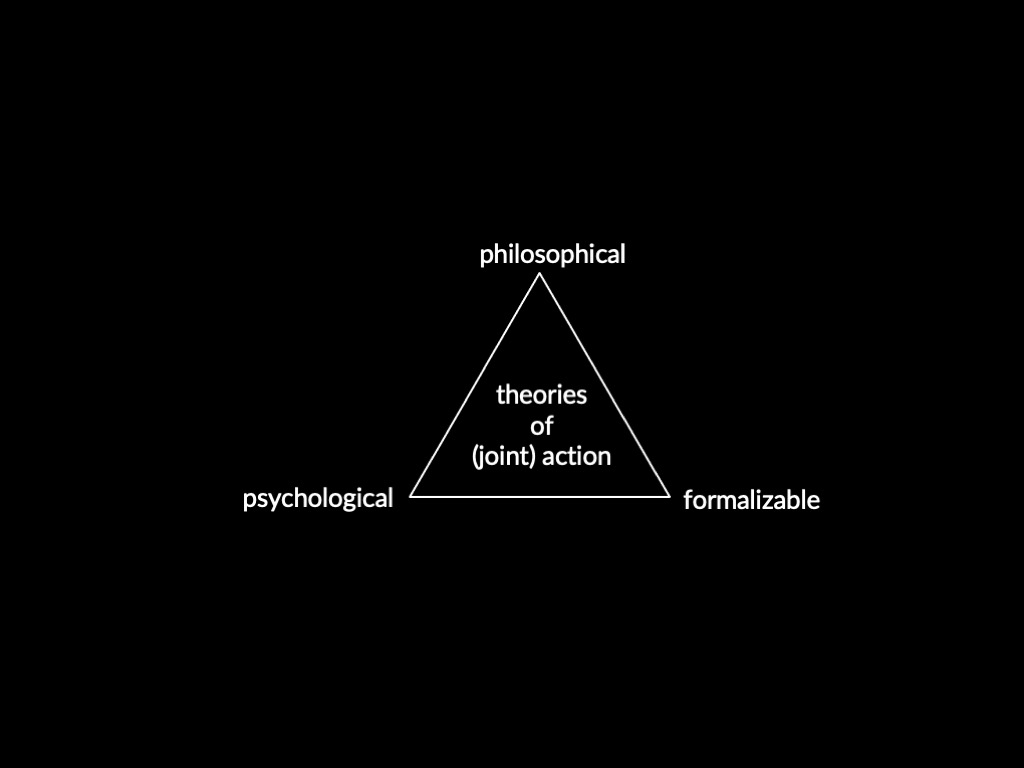

Examples and contrast cases

are just not enough

to ground a theory of joint action.

| INTENTION | yes | no |

| Is it a mental state? | Davidson (1978) | Thompson (2008) |

| Is it a belief? | Velleman (1989) | Bratman (1987) |

| Entails belief? | Harman (1976) | Levy (2018) |

| Linked to planning? | (Bratman, 1985) | |

| Incompatible with habitual? | Kalis & Ometto (2021) | |

| Entails non-observational knowledge | Anscombe (1957) | |

| Comes in two kinds? | Searle (1983) | Brozzo (2021) |

How did we get here?

Brand, 1984

a different approach

1. Which things are actions (as opposed to mere happenings)?

2. Which states or processes enable agents to act?

Which things are actions?

mechanistically committed

Those things caused by intentions are intentional actions.

Those things which are appropriately related to an intention, or to a belief-desire pair, or to some other state of an agent, are intentional actions.

...

mechanistically neutral

Those things directed to an outcome are purposive actions.

Those purposive actions which happen because of a reason favouring the outcome’s occurrence are intentional actions.

...

A goal is an outcome to which an action is directed.

Which outcomes are achievable?

For each outcome, which means of achieving it are available?

Of the various means of achieving a given outcome, which best balance cost against well-suitedness?

Of the achievable outcomes, which best balance cost against expected benefit?

Having settled on an outcome and means, when should these be maintained?

---

For an action to be directed to an outcome is for it to occur because there is one or more outcome in relation to which problems such as these have been, or appear to have been, solved.

Complications

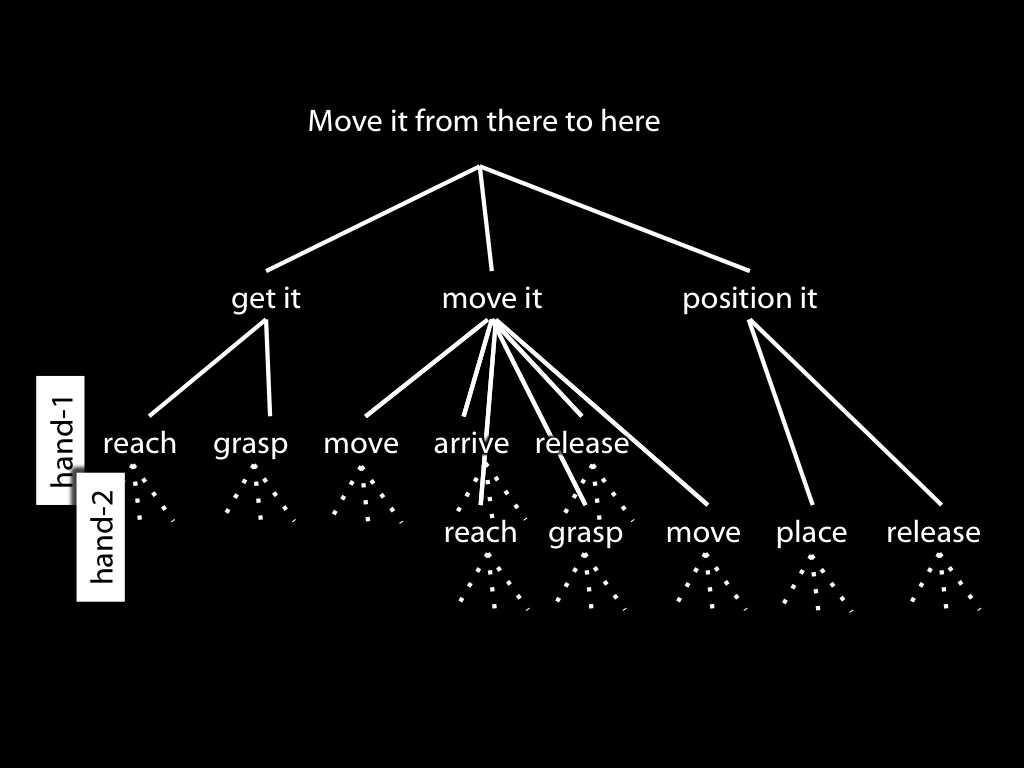

hierachical structure

overlap

1. Which things are actions (as opposed to mere happenings)?

2. Which states or processes enable agents to act?

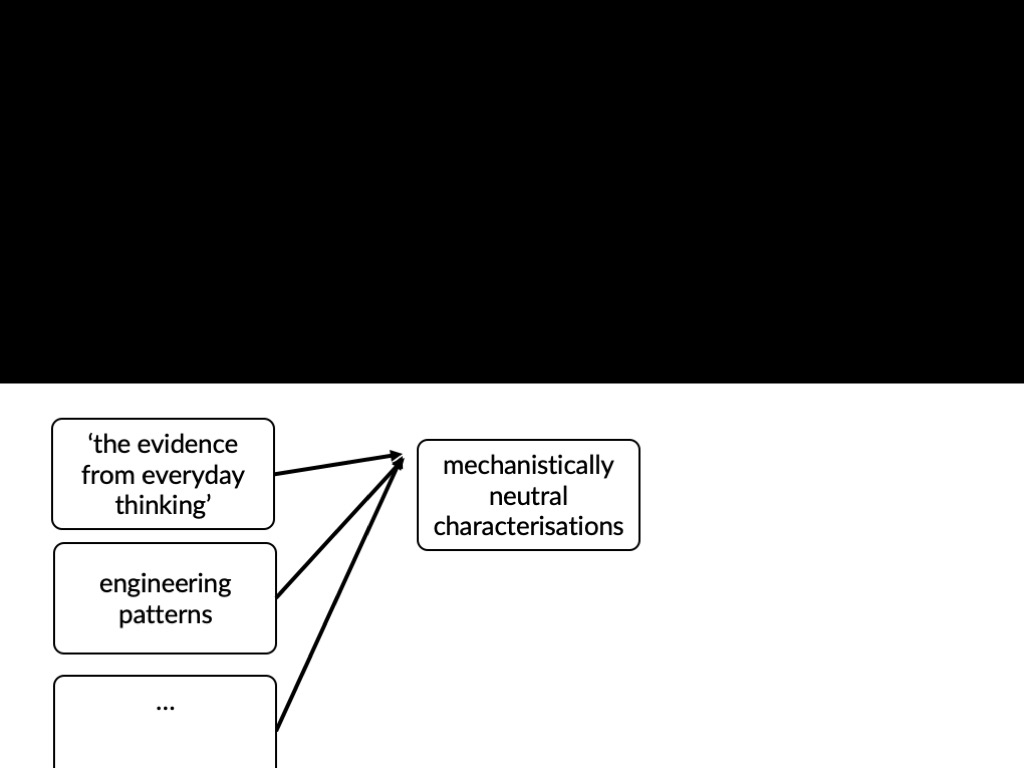

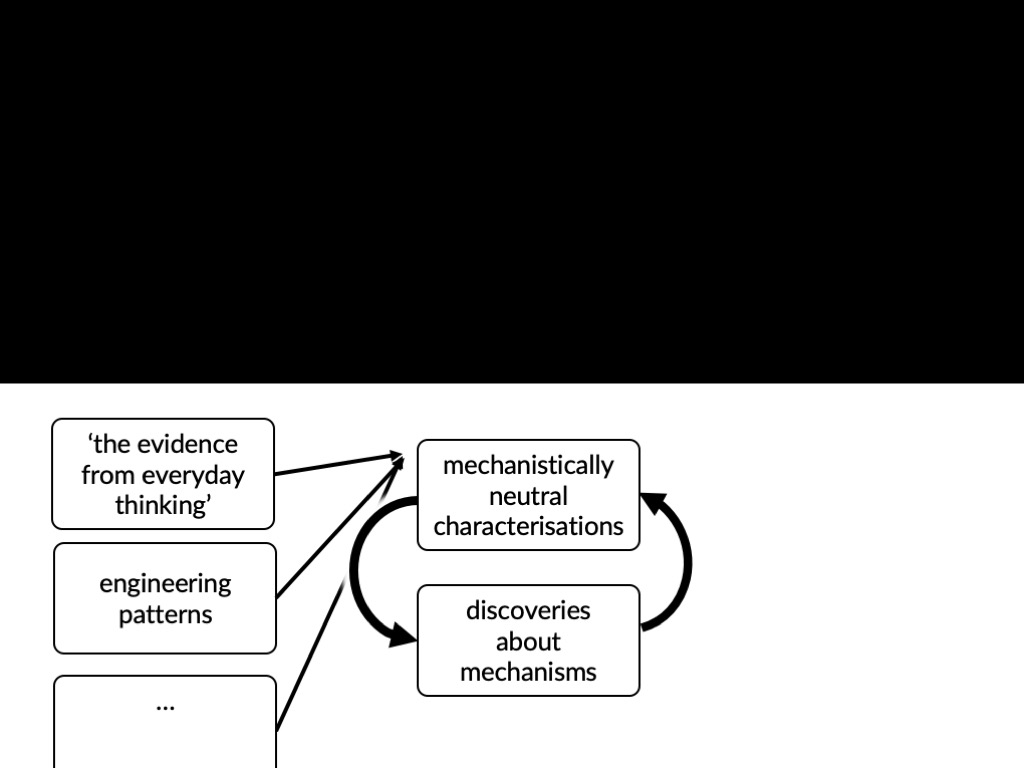

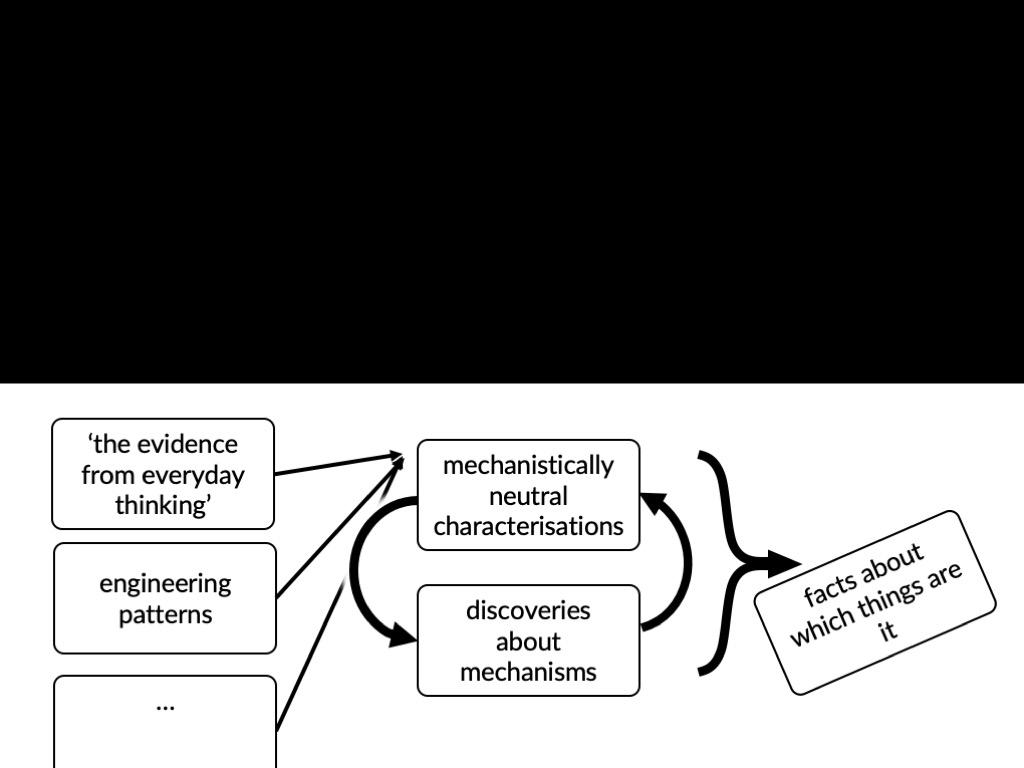

Claim: The problems used to characterise goal-directedness yield one theoretically valuable notion of action.

Jusification: This mechanistically neutral characterisation fits with discoveries about motor proceses.

Which things manifest agency?

‘The paramecium’s swimming through the beating of its cilia, in a coordinated way, and perhaps its initial reversal of direction, count as agency.’

Burge 2009 p. 259

‘the paramecium cannot be an agent [...]

None of its interactions with the environment [...] need involve anything like an act on the part of the paramecium.’

Steward 2009 p. 227

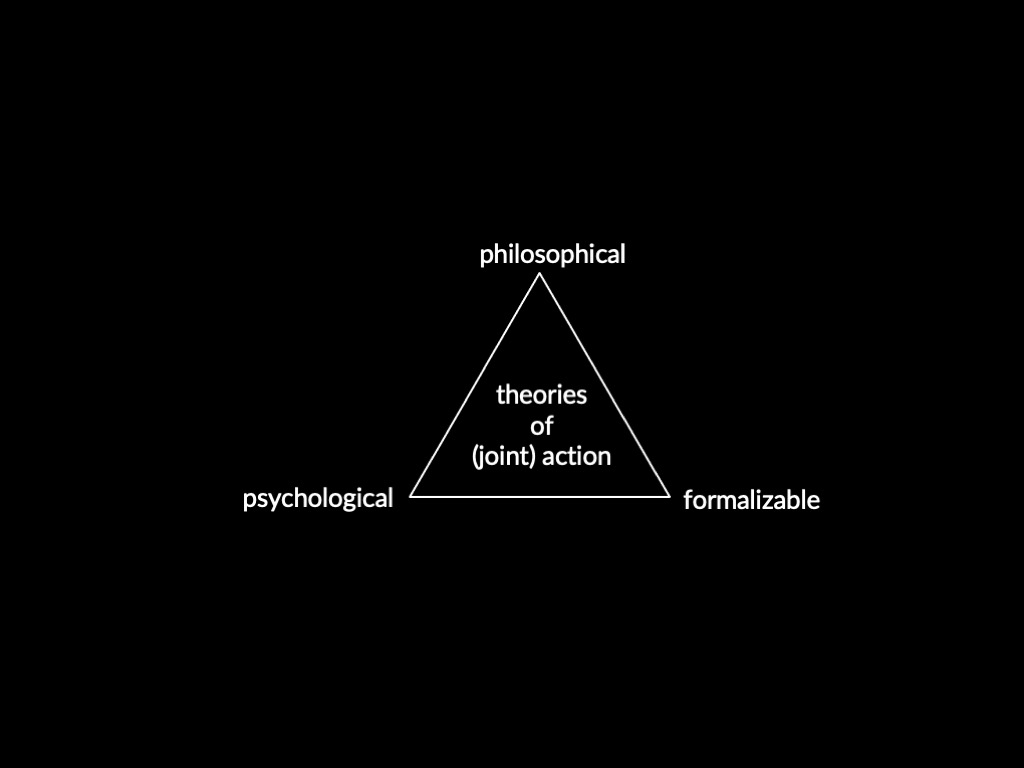

joint action

How to characterise joint action?

Step 1: identify features associated with things commonly taken to be paradigm joint actions in nonmechanistic terms, e.g.

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

- ...

Step 2: ... which generate how questions

Step 3: ... leading to discoveries about mechanisms

How to characterise joint action?

Step 1: identify features associated with things commonly taken to be paradigm joint actions in nonmechanistic terms, e.g.

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

- ...

Step 2: ... which generate how questions

Step 3: ... leading to discoveries about mechanisms

conclusion

Examples, contrast cases, counterexamples and methodological principles are probably not enough.

We need to identify features associated with things commonly taken to be paradigm (joint) actions in nonmechanistic terms.

Discoveries about mechanisms can inform us about which features belong together.

appendix

collective goals and motor representations

common goal

collective goal

‘The injections saved her life.’ [distributive vs collective]

‘The goal of their actions is to find a new home.’

Step 2: How could some agents’ actions have a collective goal?

a clue:

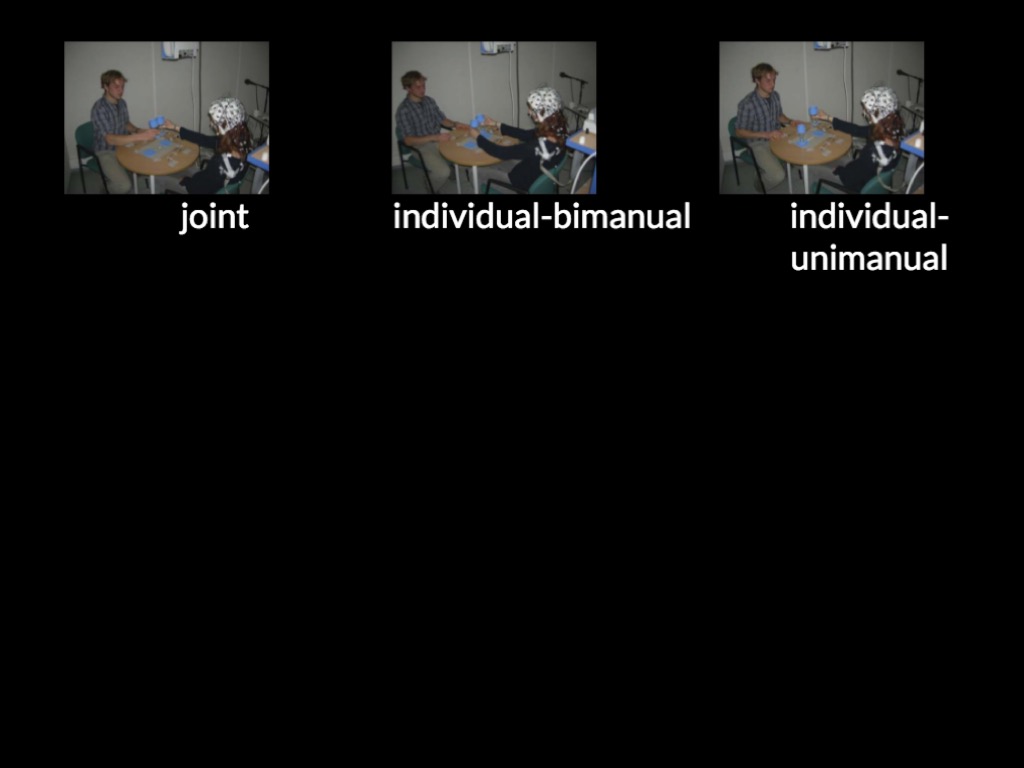

motor representations concerning

another’s actions occur in joint action

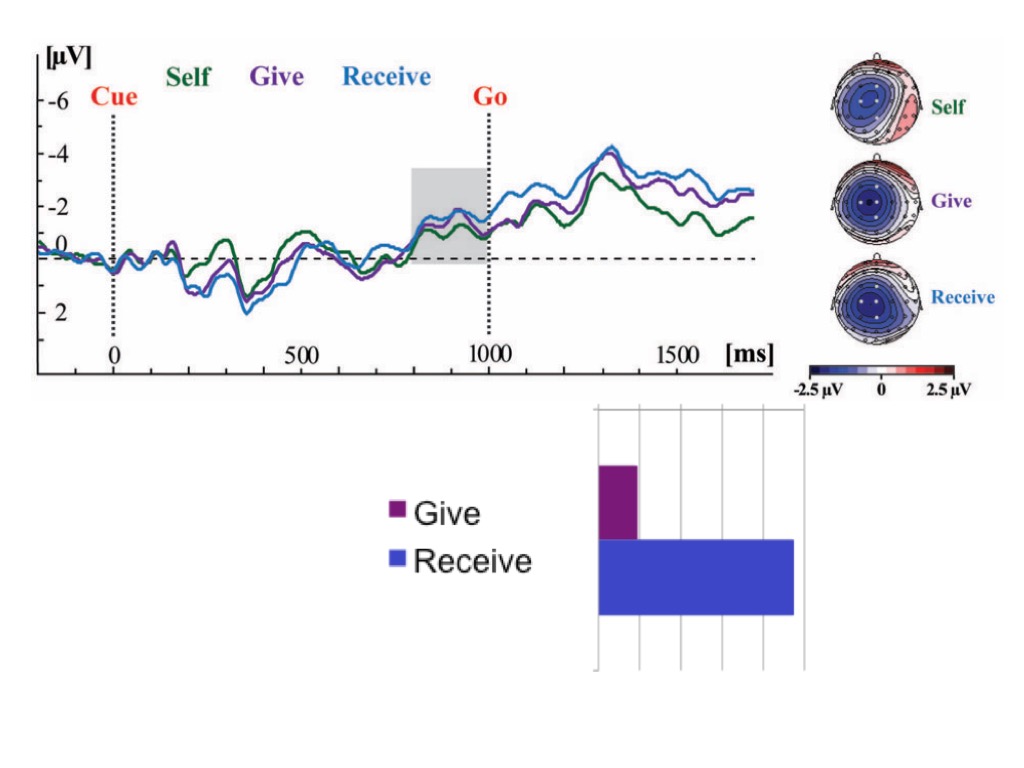

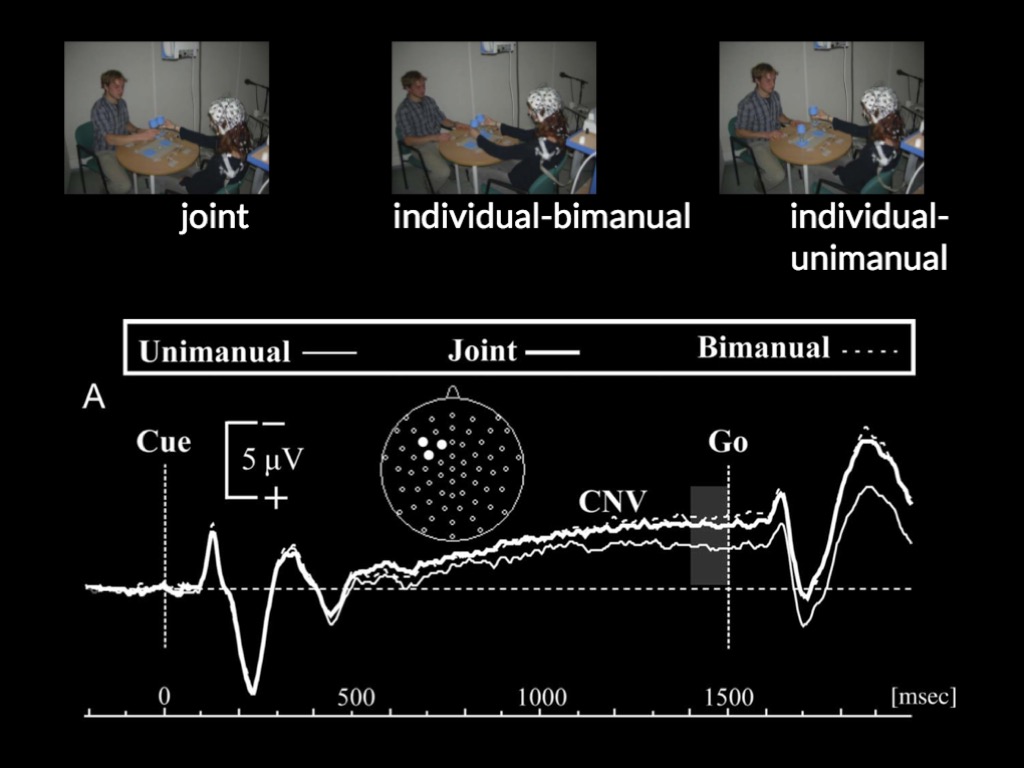

Kourtis et al, 2012

Kourtis et al, 2012

Kourtis et al, 2012

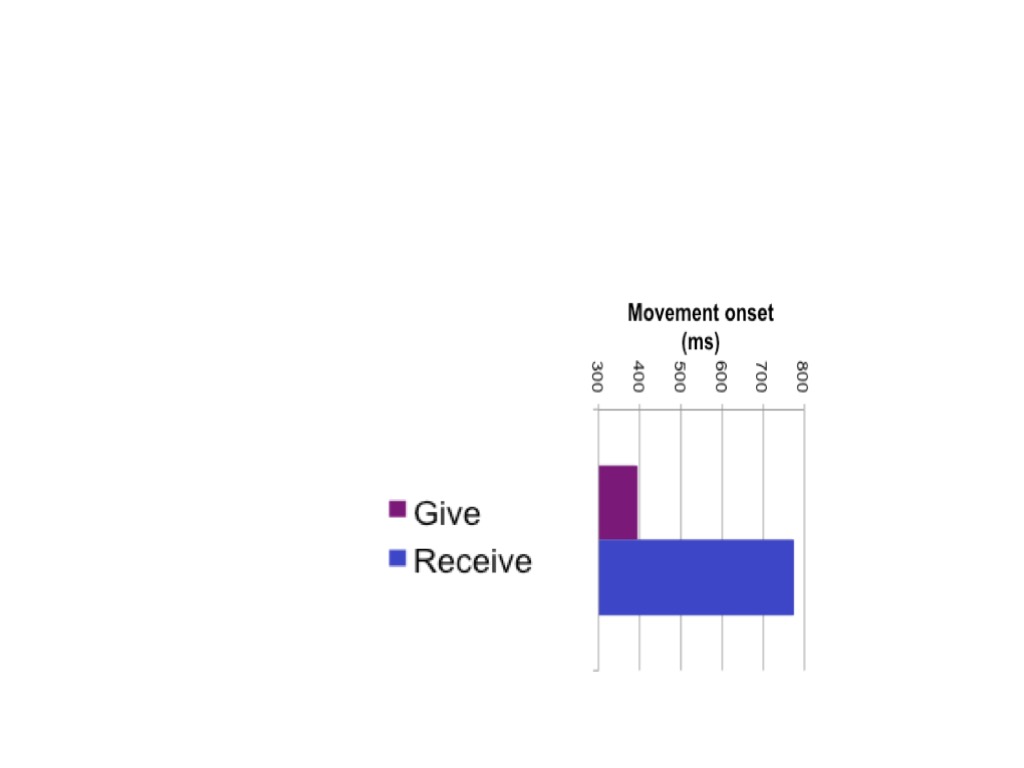

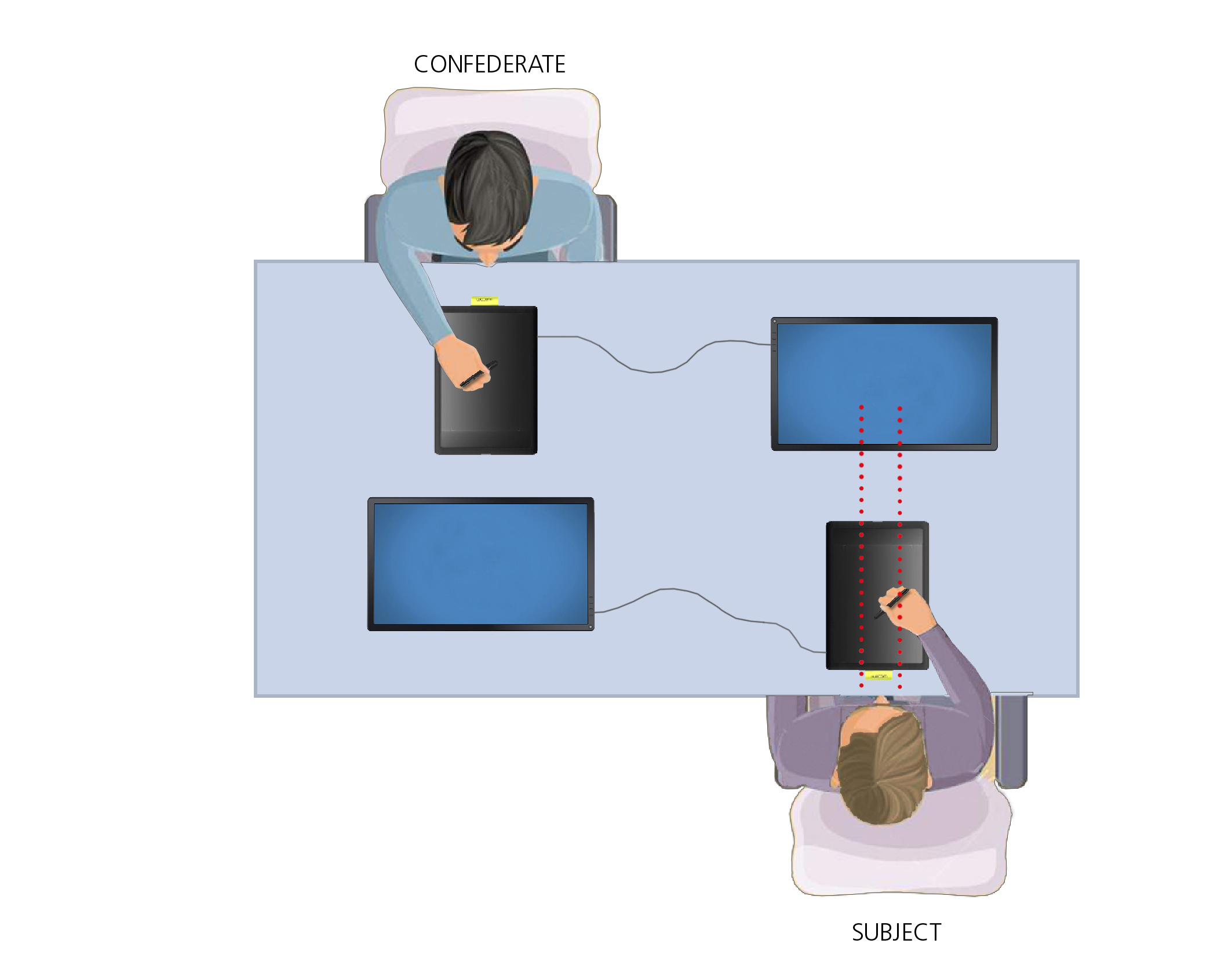

Kourtis et al (2014, figure 1c)

Kourtis et al (2014, figure 4a)

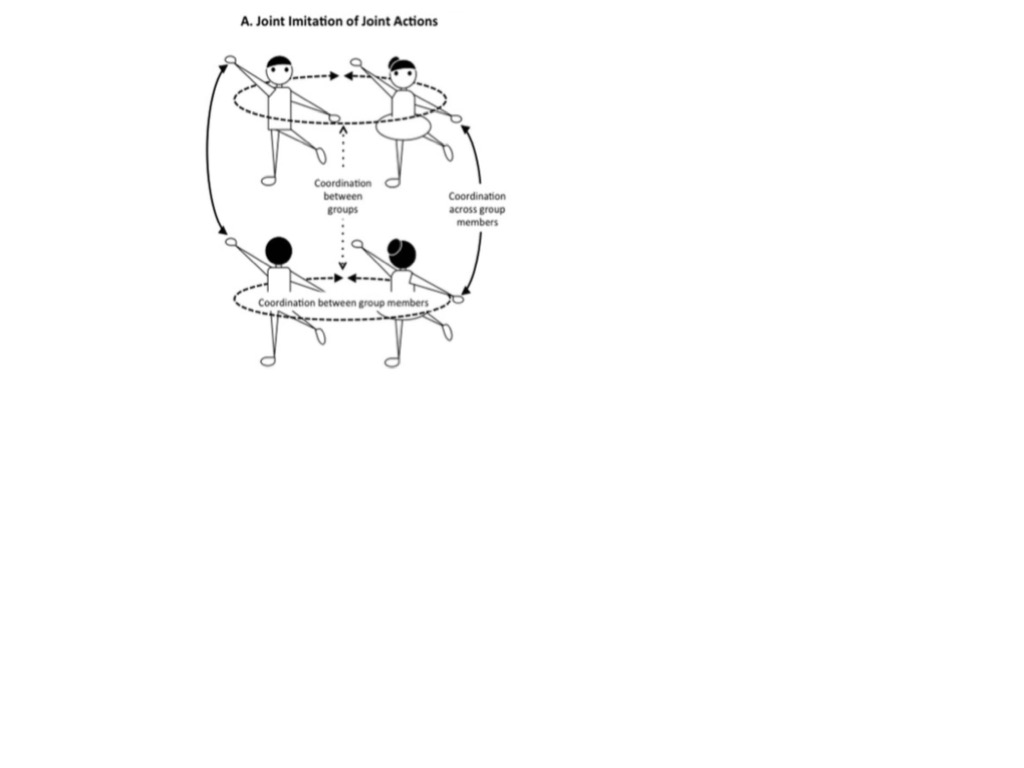

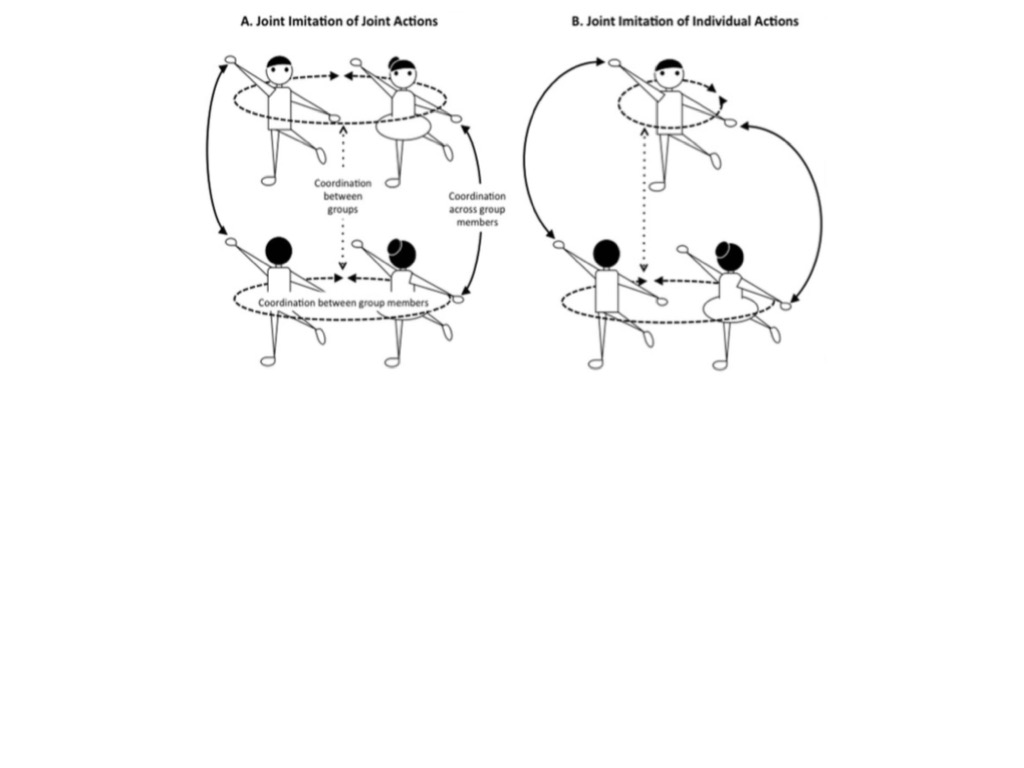

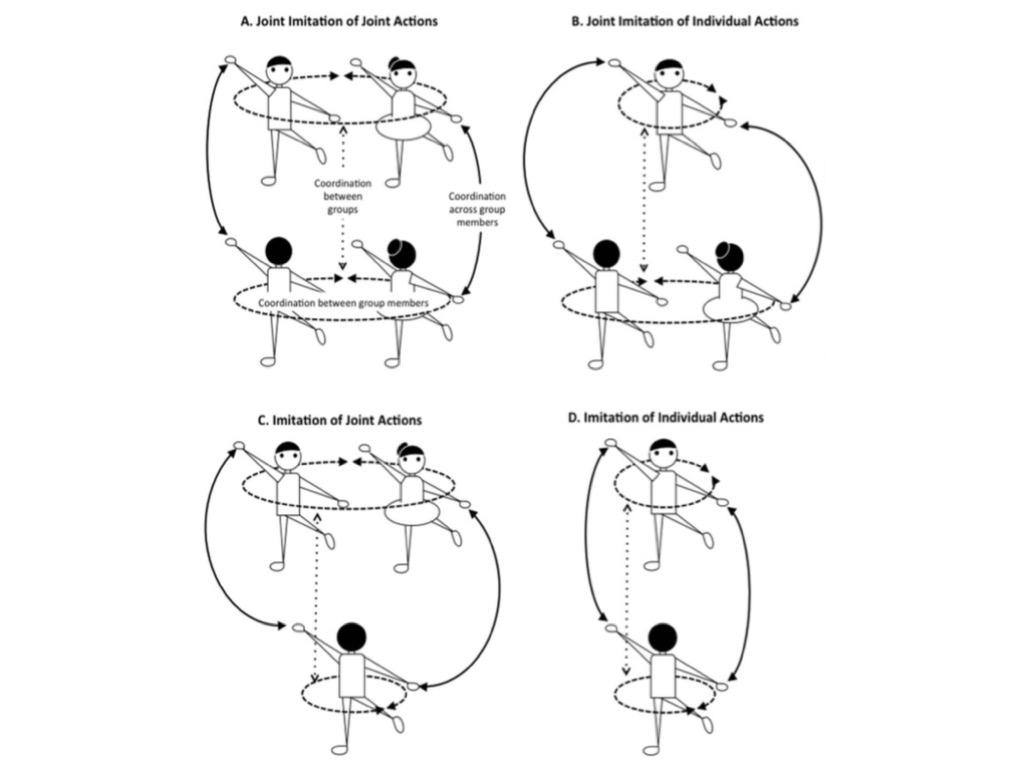

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

Ramenzoni et al, 2014 figure 1

della Gatta et al, ‘Drawn Together’ Cognition 2017

What are those motor representations doing here?

Conjecture:

Collective goals are represented motorically.

Prediction 1 (della Gatta et al, 2017):

Framing two agents’ simultaneous unimanual actions as joint can induce effects similar to bimanual coupling.

Prediction 2 (Sacheli et al):

Framing two agents’ sequential actions as a joint action modulates the effects of ‘incongruent’ actions.

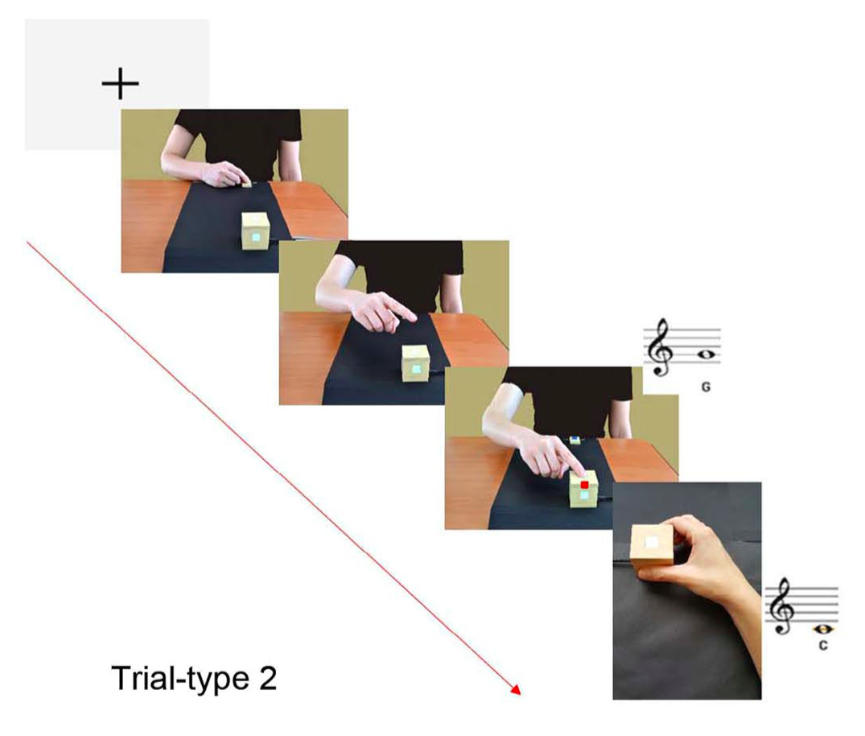

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 2 (part)

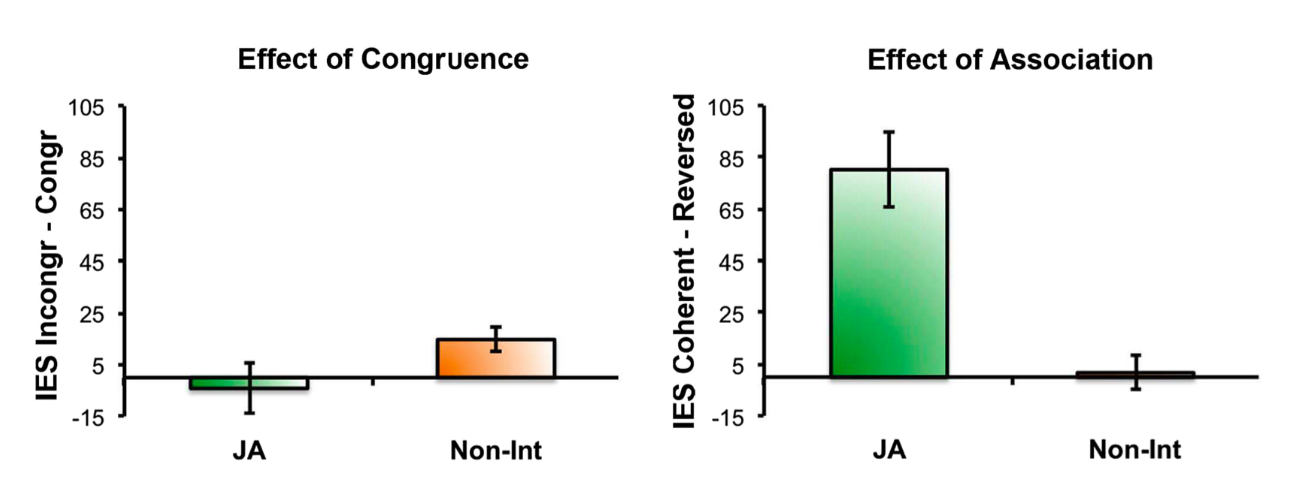

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 5

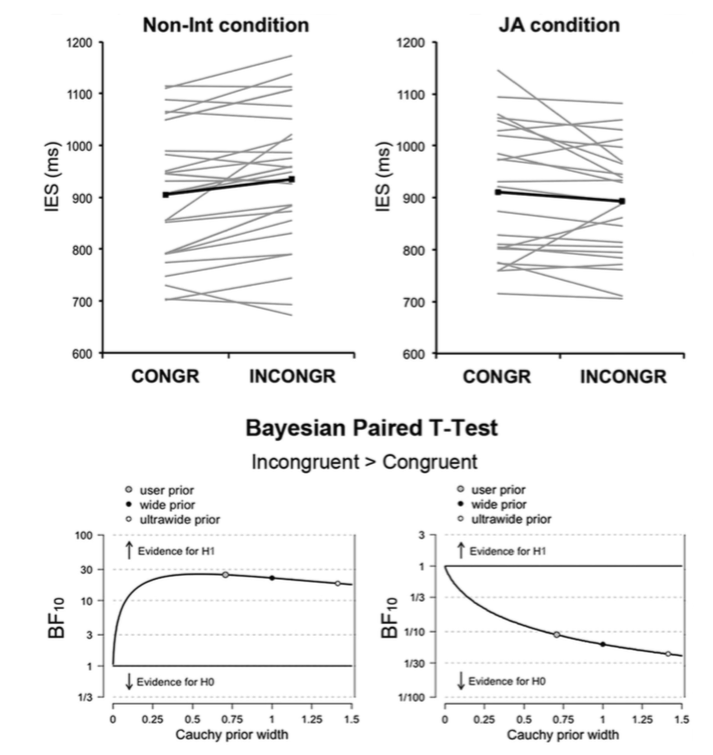

Sacheli et al, 2018 figure 3

What are those motor representations doing here?

Conjecture:

Collective goals are represented motorically.

Prediction 1 (della Gatta et al, 2017):

Framing two agents’ simultaneous unimanual actions as joint can induce effects similar to bimanual coupling.

Prediction 2 (Sacheli et al):

Framing two agents’ sequential actions as a joint action modulates the effects of ‘incongruent’ actions.

appendix

coordination

How to characterise joint action?

Step 1: identify features associated with things commonly taken to be paradigm joint actions in nonmechanistic terms, e.g.

- collective goals

- coordination

- cooperation

- contralateral commitments

- experience

- ...

Step 2: ... which generate how questions

Step 3: ... leading to discoveries about mechanisms