Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Question Session 08

this is being recorded

Alex

When it comes to the autonomy dillema, is it really the case that autonomy leads to aggregate subjects being a rare phenomena?

If so, is it influenced by an assumption that humans are more (as) likely to work for their own benefits than (as) for a groups' benefit? No!

Could one argue that a human in general is more likely to engage in team reasoning as a result of developing as a species a preference of group cooperation?

How?

aggregate subject

autonomy

‘There is ... nothing inherently inconsistent in the possibility that every member of the group has an individual preference for y over x (say, each prefers wine bars to pubs) while the group acts on an objective that ranks x above y.’

(Sugden, 2000)

dilemma

autonomy -> rare for team reasoning to occur because axioms

no autonomy -> no aggregate subject after all (just cooperative games)

transitivity

For any A, B, C ∈ S: if A⪯B and B⪯C then A⪯C.

completeness

For any A, B ∈ S: either A⪯B or B⪯A

continuity

‘Continuity implies that no outcome is so bad that you would not be willing to take some gamble that might result in you ending up with that outcome [...] provided that the chance of the bad outcome is small enough.’

independence

roughly, if you prefer A to B then you should prefer A and C to B and C.

Steele & Stefánsson (2020, p. §2.3)

For an aggregate agent comprising me and you to reliably satisfy these axioms

- we must agree on what its preferences are

- we must nonaccidentally coincide on when each of us is when each of us is acting as part of the aggregate (rather than individually)

- whenever any of us unilaterally attempts to influence what its preferences are by acting, we must succeed in doing so

- ...

Alex

When it comes to the autonomy dillema, is it really the case that autonomy leads to aggregate subjects being a rare phenomena?

If so, is it influenced by an assumption that humans are more (as) likely to work for their own benefits than (as) for a groups' benefit? No!

Could one argue that a human in general is more likely to engage in team reasoning as a result of developing as a species a preference of group cooperation?

autonomy

‘There is ... nothing inherently inconsistent in the possibility that every member of the group has an individual preference for y over x (say, each prefers wine bars to pubs) while the group acts on an objective that ranks x above y.’

(Sugden, 2000)

dilemma

autonomy -> rare for team reasoning to occur because axioms

no autonomy -> no aggregate subject after all (just cooperative games)

Alex

When it comes to the autonomy dillema, is it really the case that autonomy leads to aggregate subjects being a rare phenomena?

If so, is it influenced by an assumption that humans are more (as) likely to work for their own benefits than (as) for a groups' benefit? No!

Could one argue that a human in general is more likely to engage in team reasoning as a result of developing as a species a preference of group cooperation?

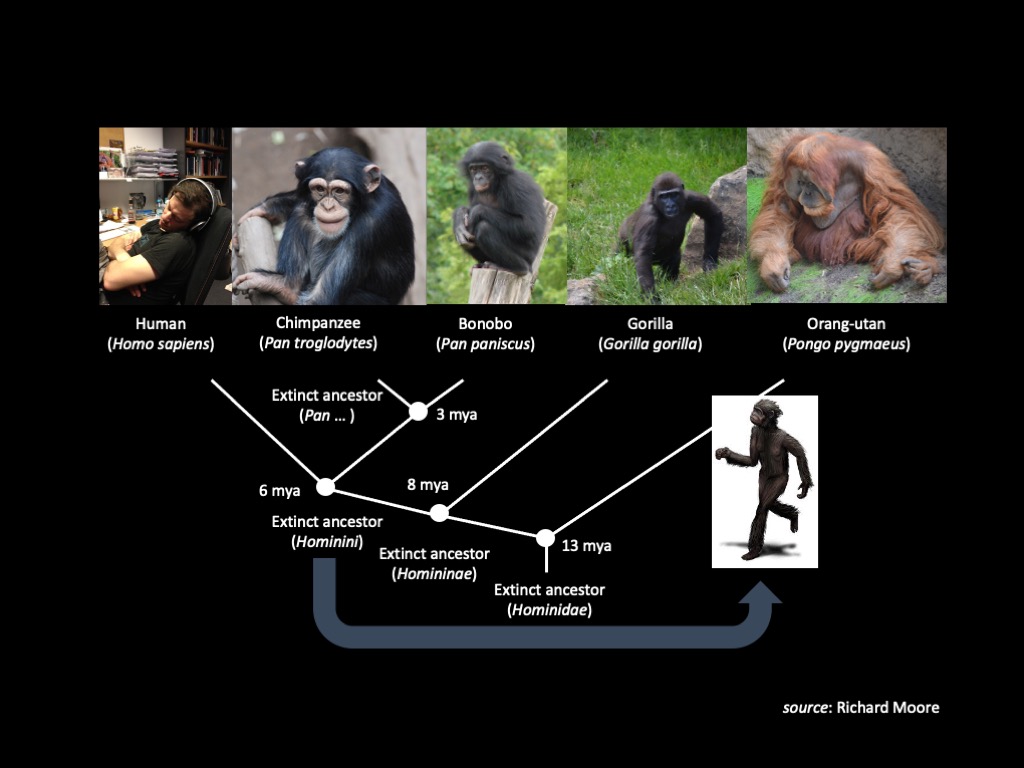

‘There have been two revolutions in human social life [...].

The first is the transition from great ape social lives to those of the egalitarian foraging bands of the mid- to late-Pleistocene. [...] The transition from great ape to forager social life took millions of years. [...]

Around 10 kya, at the Pleistocene–Holocene transition, a second social revolution began, with the transition to farming and to a sedentary society,’

(Sterelny, 2016)

Alex

When it comes to the autonomy dillema, is it really the case that autonomy leads to aggregate subjects being a rare phenomena?

If so, is it influenced by an assumption that humans are more (as) likely to work for their own benefits than (as) for a groups' benefit? No!

Could one argue that a human in general is more likely to engage in team reasoning as a result of developing as a species a preference of group cooperation?

- Sterelny (2016)

1

a ‘cooperator is someone who pays a cost, c, for another individual to receive a benefit, b’

(Nowak 2006, p. 1560).

2

‘[b]y cooperation we mean engaging with others in a mutually beneficial activity’ (Bowles & Gintis 2011, p. 2)

‘Cooperation appears in nature in two basic forms’ (Tomasello)

3

(~Bratman, 1992; 2015).

‘A definition of cooperation ... typically [has this] structure: a set of individual intentions [with] certain origins and ... certain relations, ... is common knowledge’

(Paternotte 2014, p. 47)

What are the different candidate notions of cooperation?

In which explanations do any of these notions of cooperation feature ?

(example: Sterelny, 2016)

How, if at all, does team reasoning link to any of these notions of cooperation?

Alex

When it comes to the autonomy dillema, is it really the case that autonomy leads to aggregate subjects being a rare phenomena?

If so, is it influenced by an assumption that humans are more (as) likely to work for their own benefits than (as) for a groups' benefit? No!

Could one argue that a human in general is more likely to engage in team reasoning as a result of developing as a species a preference of group cooperation?

- Sterelny (2016)

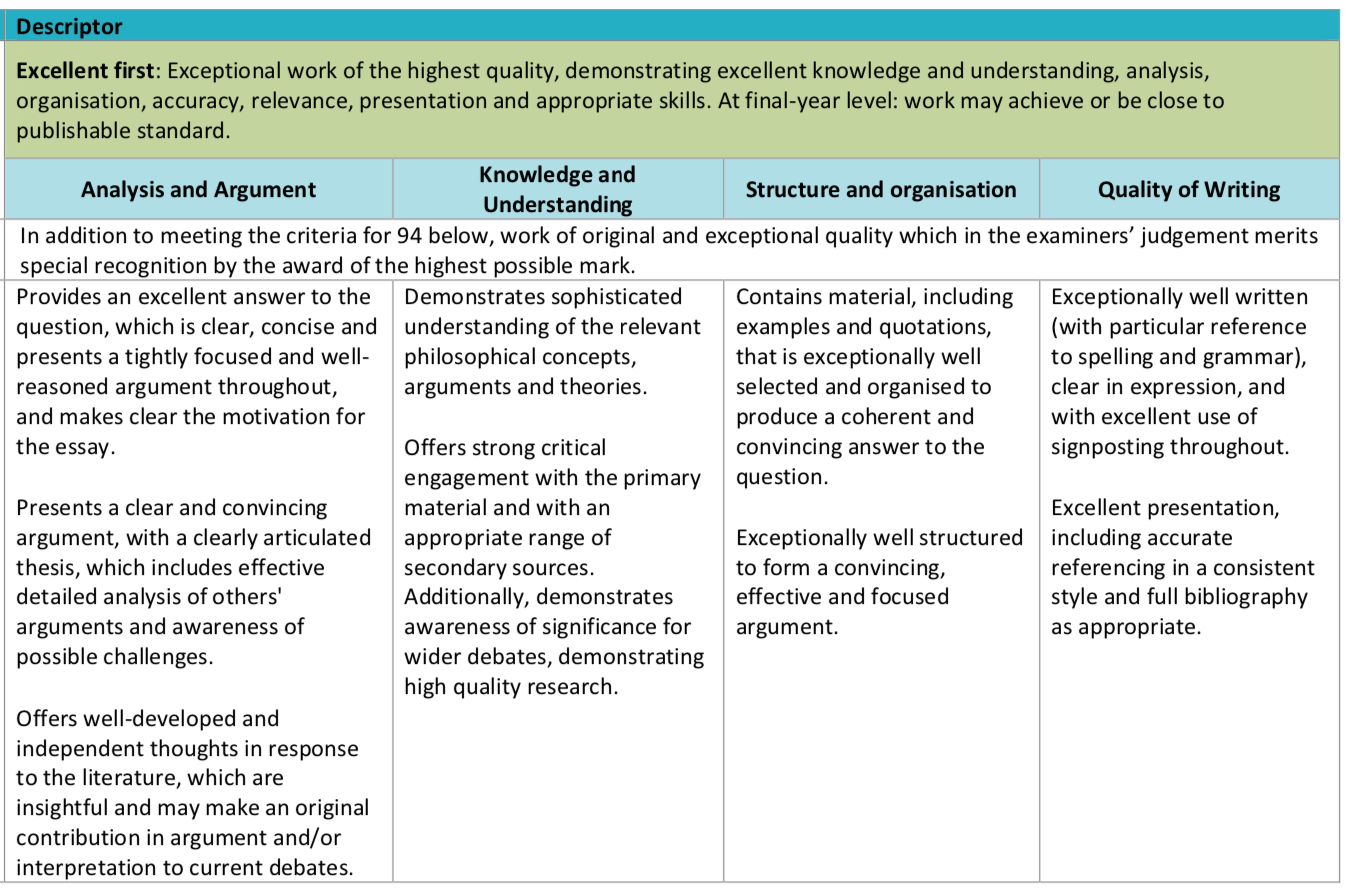

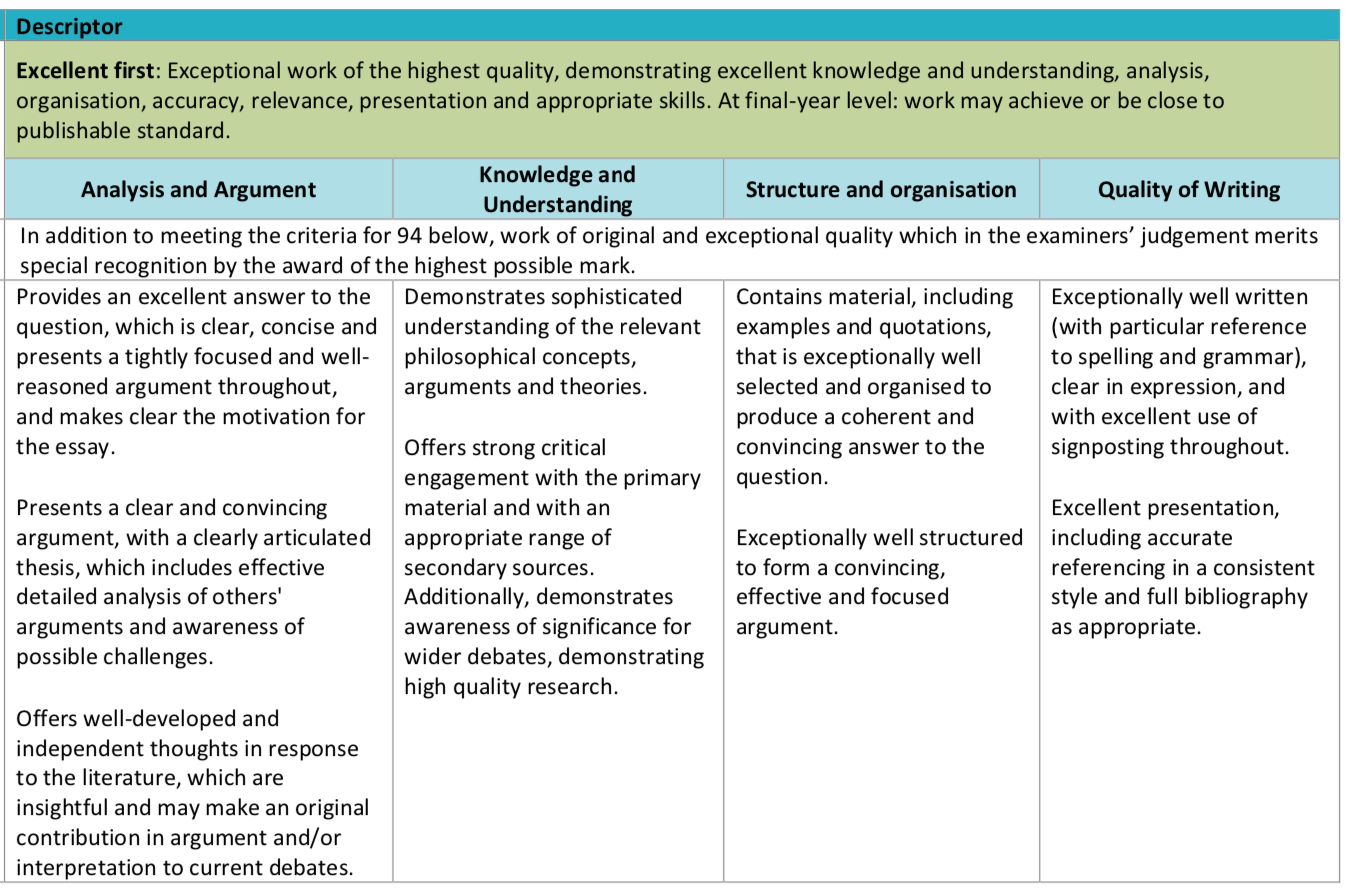

long essay topics

https://philosophical-issues-in-behavioural-science.butterfill.com/pdf/essay_questions.pdf

‘What is an interface problem?

Consider one case in which an interface problem arises.

How could the problem be solved?’

‘What is an interface problem?

‘What is an interface problem?

another question

How, if at all, should a philosophical theory of acting together incorporate scientific discoveries about the interpersonal coordination of action?

What are the aims of a philosophical theory of acting together?

What are some of the discoveries?

option 1: Say how have some researchers claimed they are relevant. Why are those researchers wrong?

option 2: Introduce a philosophical theory with these aims (e.g. Bratman’s) and explain how the discoveries are relevant to it. What are the implications?

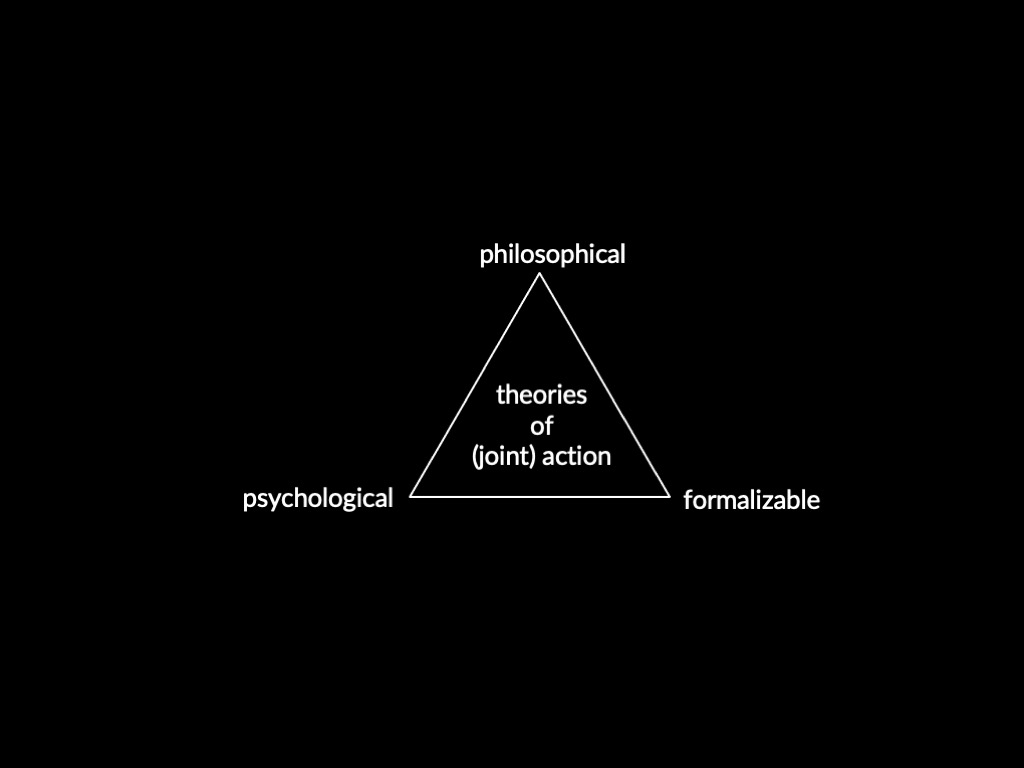

Why mix the three (philosophical, psychological and formal)?

philosophical

methods

informally observing,

guessing (‘intuition’),

imagining counterfactual situations

(‘thought experiments’),

reasoning,

& pursuing theoretical elegance

| INTENTION | yes | no |

| Is it a mental state? | Davidson (1978) | Thompson (2008) |

| Is it a belief? | Velleman (1989) | Bratman (1987) |

| Entails belief? | Harman (1976) | Levy (2018) |

| Linked to planning? | (Bratman, 1985) | |

| Incompatible with habitual? | Kalis & Ometto (2021) | |

| Entails non-observational knowledge | Anscombe (1957) | |

| Comes in two kinds? | Searle (1983) | Brozzo (2021) |

Philosophical Folk Psychology

‘epistemic case intuitions are generated by [...] folk psychology’

Nagel (2012, p. 510)

As philosophers see

folk psychology ...

‘When someone is in so-and-so combination of mental states and receives sensory stimuli of so-and-so kind, he tends with so-and-so probability to be caused thereby to go into so-and-so mental states and produce so-and-so motor responses.’

(Lewis, 1972, p. 256)

(my|your|his|her|their) phone

is trying to (excluding ‘kill me’) [283,000]

wants to [278,000]

hates [147,000]

likes [86,800]

thinks (e.g. ‘My phone thinks I’m in another city’) [53,400]

is pretending [16,000]

Is

folk psychology

a source of common knowledge of principles

that implicitly define ‘intention’, ‘knowledge’, and the rest

?

Lewis (1972) vs Heider (1958)

Two obstacles

- many incompatible theories, each only slightly different from nearby alterantives

- differences hard to operationalize

Philosophical accounts of minds and actions ...

... anchor a shared understanding of what intention, preference, belief, and the rest are.

... could be (mis)used to characterise various models of mind.

more questions?