Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Question Session 06

this is being recorded

What anchors our shared understanding, as researchers, of

agents, actions, beliefs, desires, intentions and the like?

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

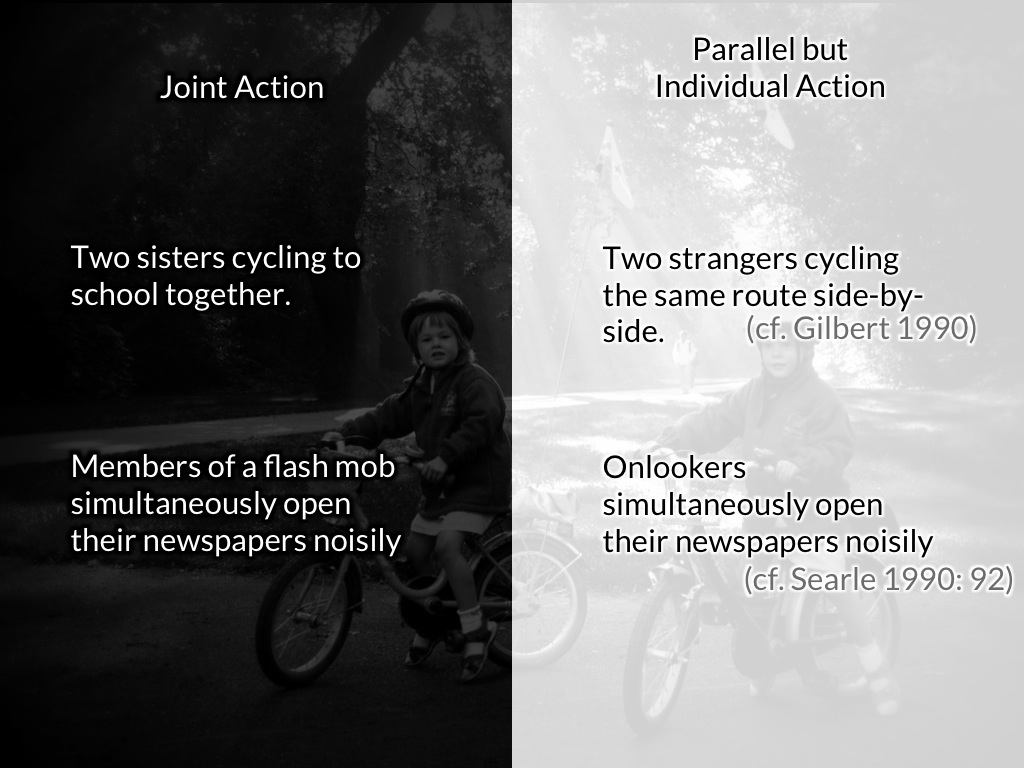

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

What anchors our shared understanding, as researchers, of

agents, actions, beliefs, desires, intentions and the like?

What distinguishes your actions from things that merely happen to you? (‘The Problem of Action’)

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Which things manifest agency?

‘The paramecium’s swimming through the beating of its cilia, in a coordinated way, and perhaps its initial reversal of direction, count as agency.’

(Burge, 2009, p. 259)

‘the paramecium cannot be an agent [...]

None of its interactions with the environment [...] need involve anything like an act on the part of the paramecium.’

(Steward, 2009, p. 227)

Do these two have a shared understanding of agency?

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

What anchors our shared understanding, as researchers, of

agents, actions, beliefs, desires, intentions and the like?

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

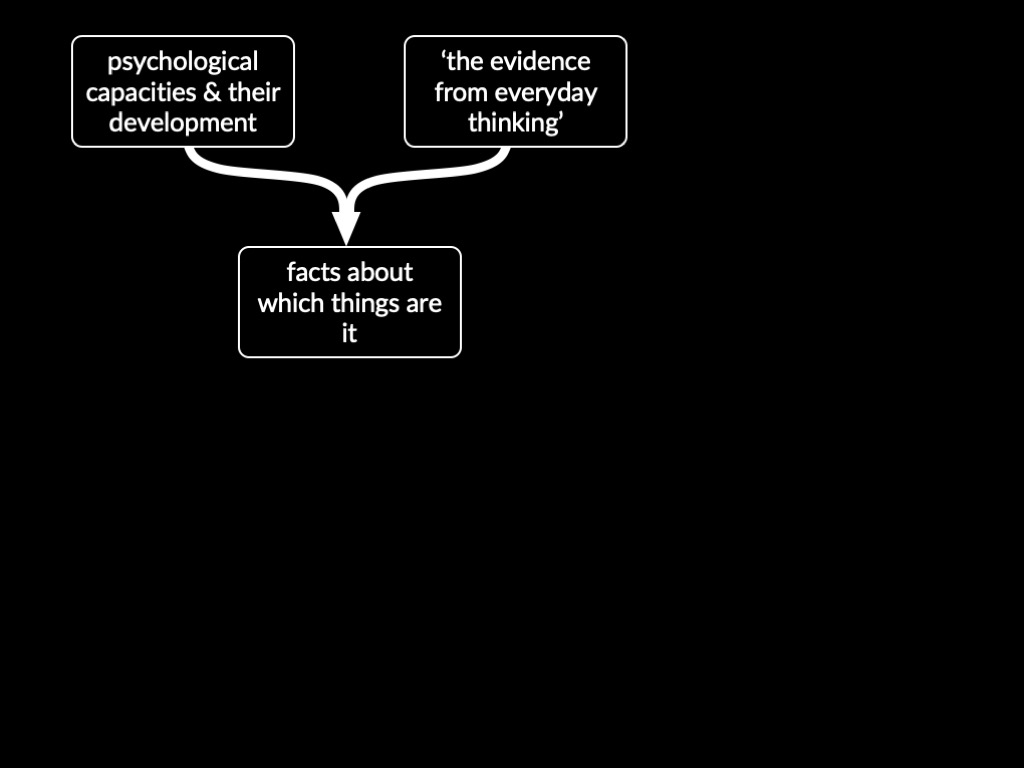

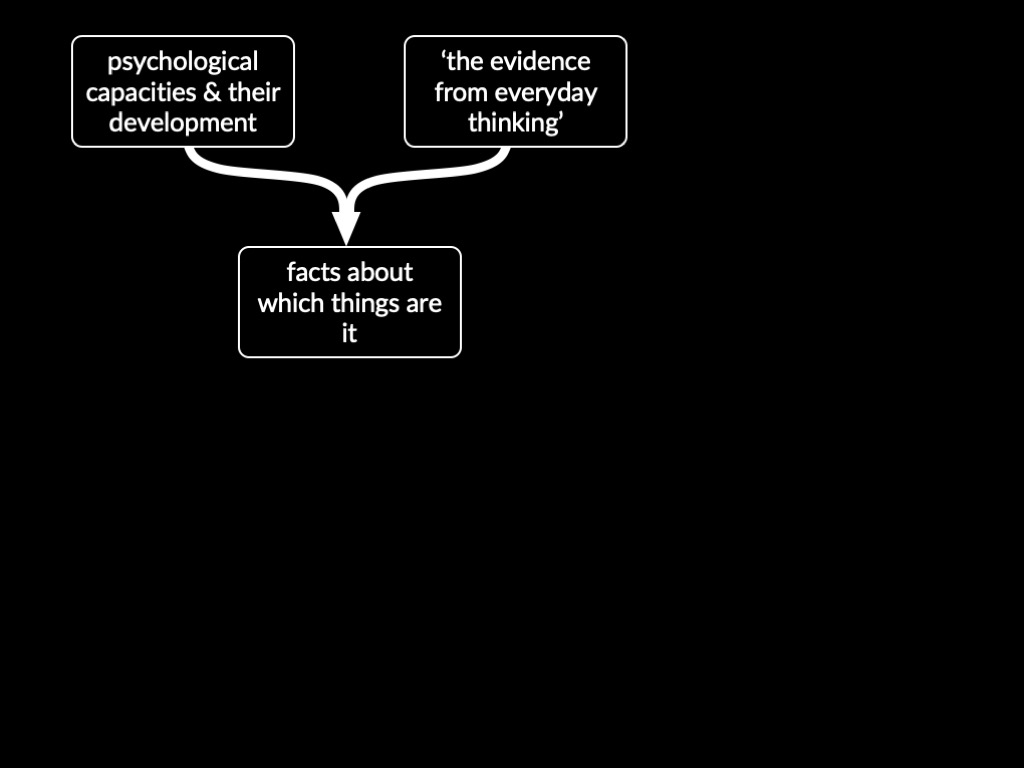

Early-developing (or innate) psychological capacities enable us to track agents red things.

There is ‘everyday thinking’ about red things.

But neither straightforwardly supports conclusions about which things are red.

‘The reds in

red hair, red potatoes, red cabbage, red bell peppers, red onions, red grapes, red beans, red wine, and red skin

[...] only make sense with the similarity, preference, and exhaustiveness constraints. And these constraints couldn't work if it weren't for the principle of possibilities’

(Clark, 1992, p. 372)

‘the principle of possibilities: We understand what an entity is with reference to [...] the set of possibilities we infer it came from’

As with colour, psychological terms like ‘acts’ and ‘thinks’ can be used to make many different contrasts ...

‘I know that my orchids are trying to stave off the cold so they can get growing again’

‘This dormancy happens because the grass is trying to preserve itself with limited resources’

‘spotify is trying to play’

‘as the flight controller fights to hold the craft in what it thinks is the correct attitude’

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

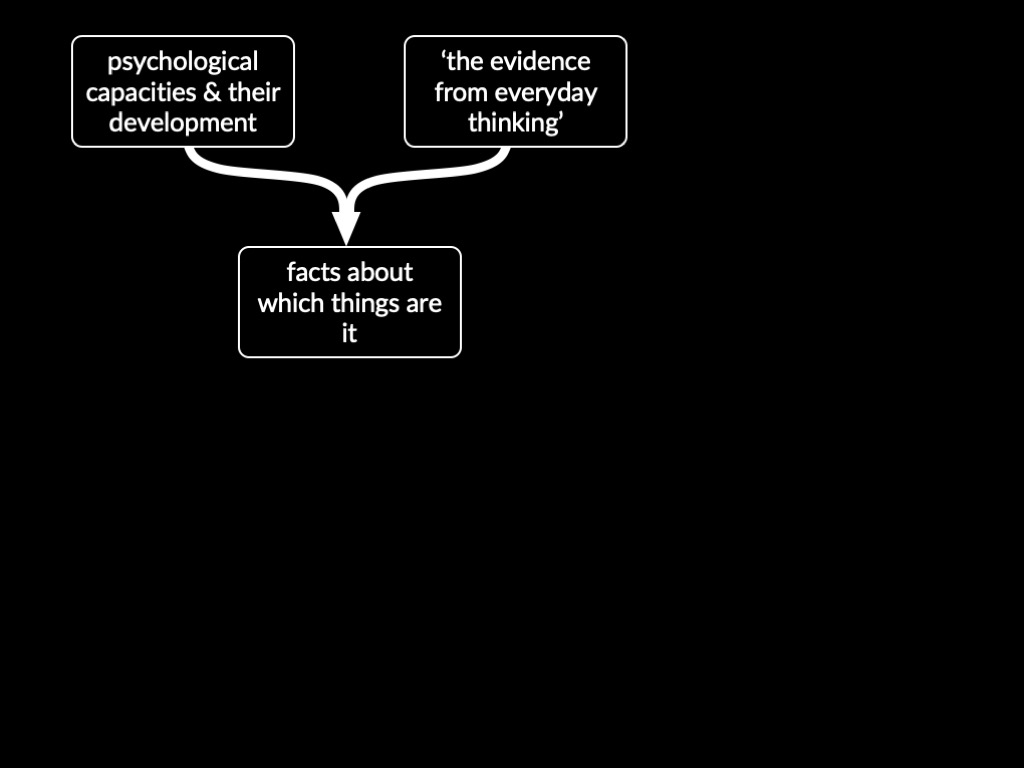

Early-developing (or innate) psychological capacities enable us to track agents red things.

There is ‘everyday thinking’ about red things.

But neither straightforwardly supports conclusions about which things are red.

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

(my|your|his|her|their) phone

is trying to (excluding ‘kill me’) [283,000]

wants to [278,000]

hates [147,000]

likes [86,800]

thinks (e.g. ‘My phone thinks I’m in another city’) [53,400]

is pretending [16,000]

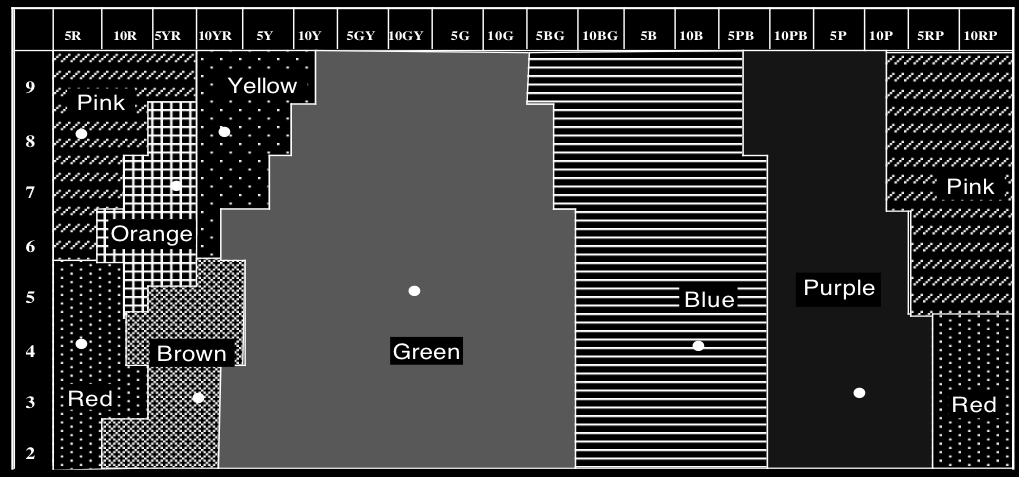

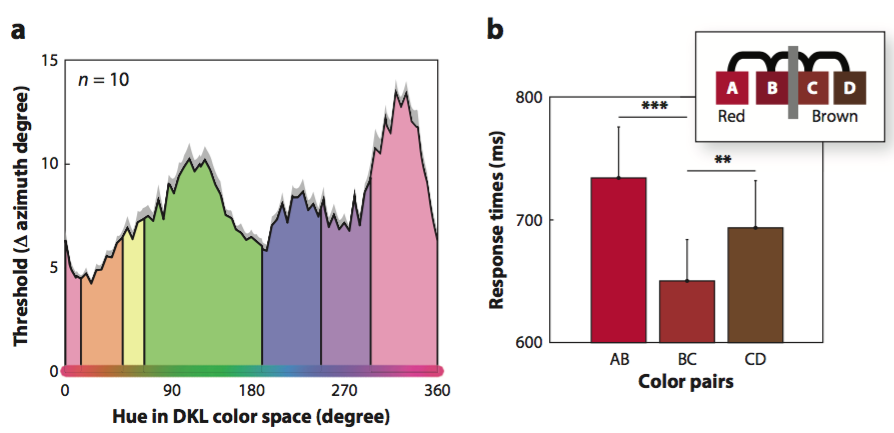

reply : but there are paradigm cases

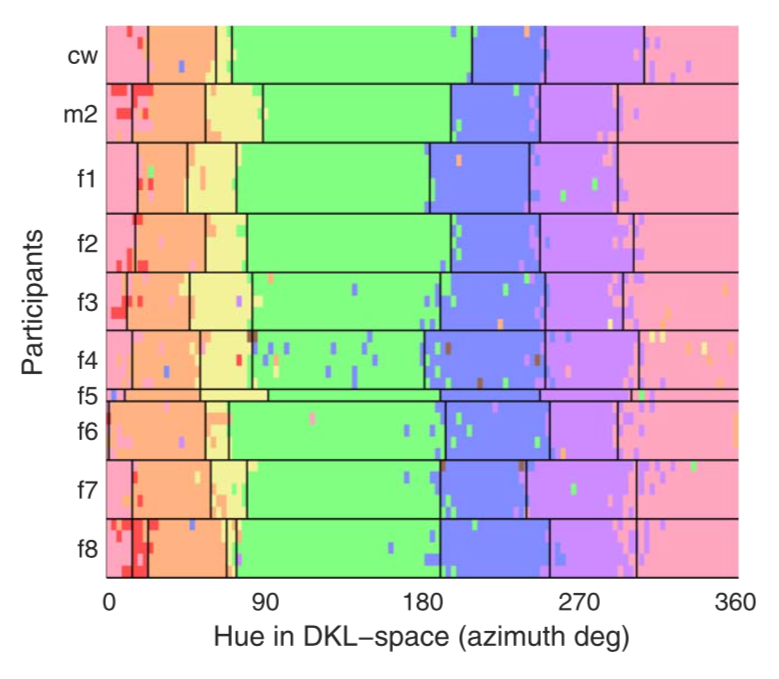

Witzel & Gegenfurtner, 2013 figure 6

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

Objection: Compare ‘red’ things: Which concept?

Reply: paradigm cases

Objection-to-Reply: ???

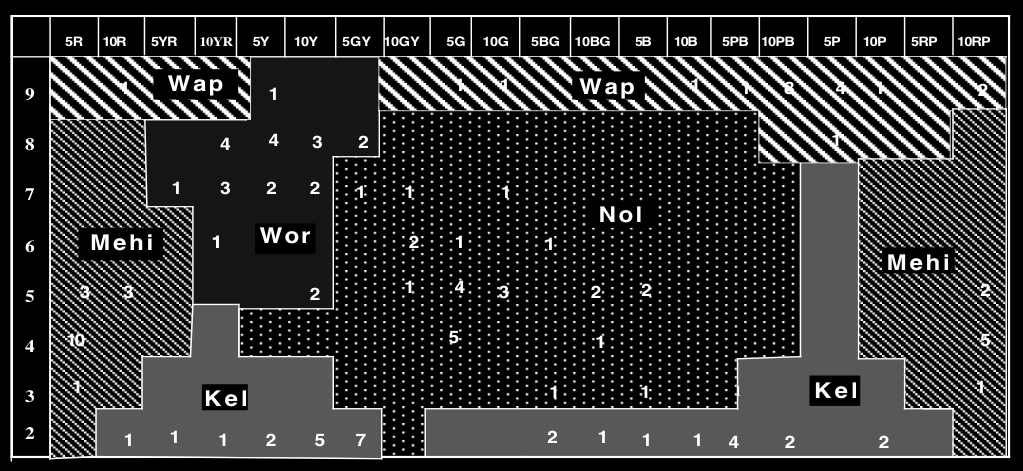

English

Roberson & Hanley 2010, Figure 1c

Berinmo

Roberson & Hanley 2010, Figure 1b

cross-cultural differences on action?

‘While diverse thoughts, opinions, and beliefs may not be a strong feature of ni-Vanuatu children’s conversational environments, social emotions (e.g., shame, resentment, jealousy, empathy, mutual happiness, and so forth) are more commonly and readily invoked in order to describe, predict, and explain behavior’

Dixson, Komugabe-Dixson, Dixson, & Low (2018, p. 2171)

further reading: Wassmann, Funke, & Träuble (2013)

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

Objection: Compare ‘red’ things: Which concept?

Reply: paradigm cases

Objection-to-Reply:

cultural variation -> whose paradigms?

and ???

Witzel & Gegenfurtner 2018, figure 5

We can ‘ask the normative question whether the concept truly applies to creatures of a given sort. The concept, once formed, has its own integrity’

Steward, 2009 p. 227

Objection: Compare ‘red’ things: Which concept?

Reply: paradigm cases

Objection-to-Reply:

cultural variation -> whose paradigms?

and multiple mechanisms

-> which paradigms?

What anchors our shared understanding, as researchers, of

agents, actions, beliefs, desires, intentions and the like?

What anchors our shared understanding, as researchers, of

agents, actions, beliefs, desires, intentions and the like?

Brand, 1984

more questions?