Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Togetherness vs the Simple Theory of Joint Action

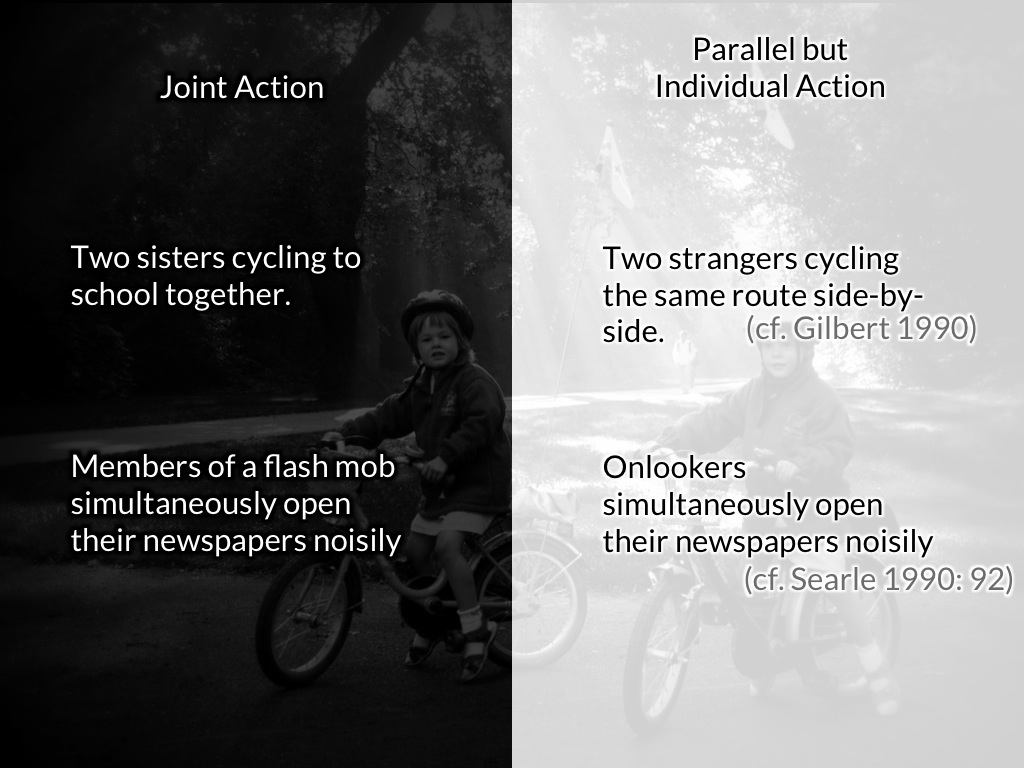

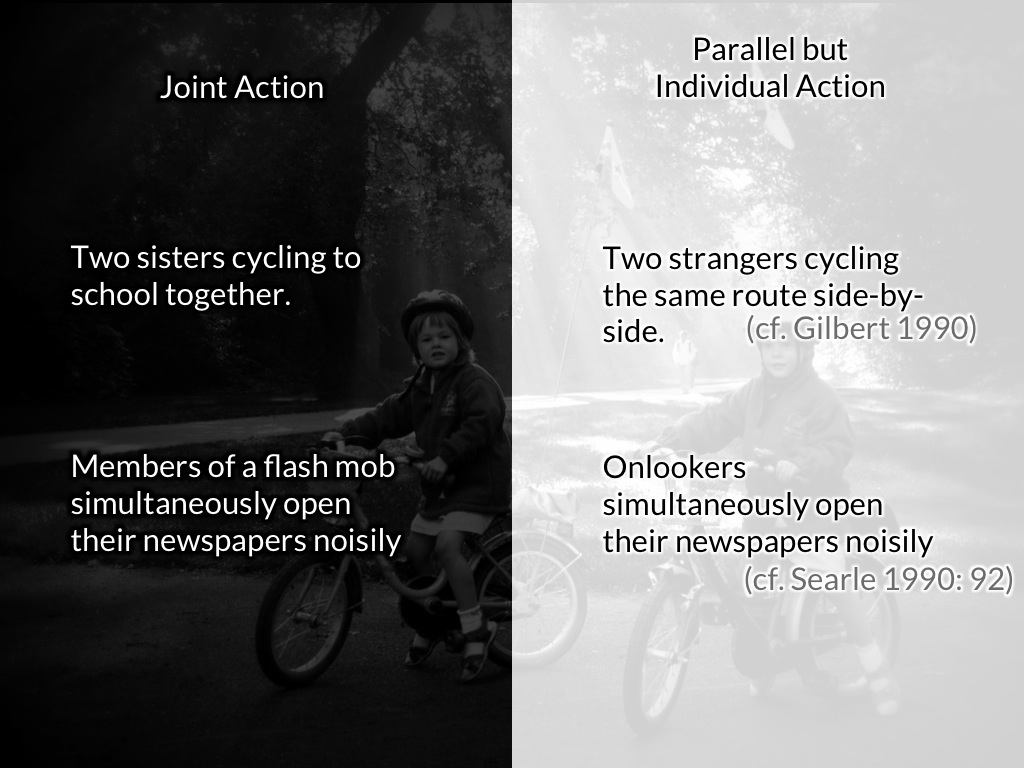

The Simple Theory

Two or more agents perform an intentional joint action

exactly when there is an act-type, φ, such that

each agent intends that

they, these agents, φ together

and their intentions are appropriately related to their actions.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

Contrast:

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school apart.

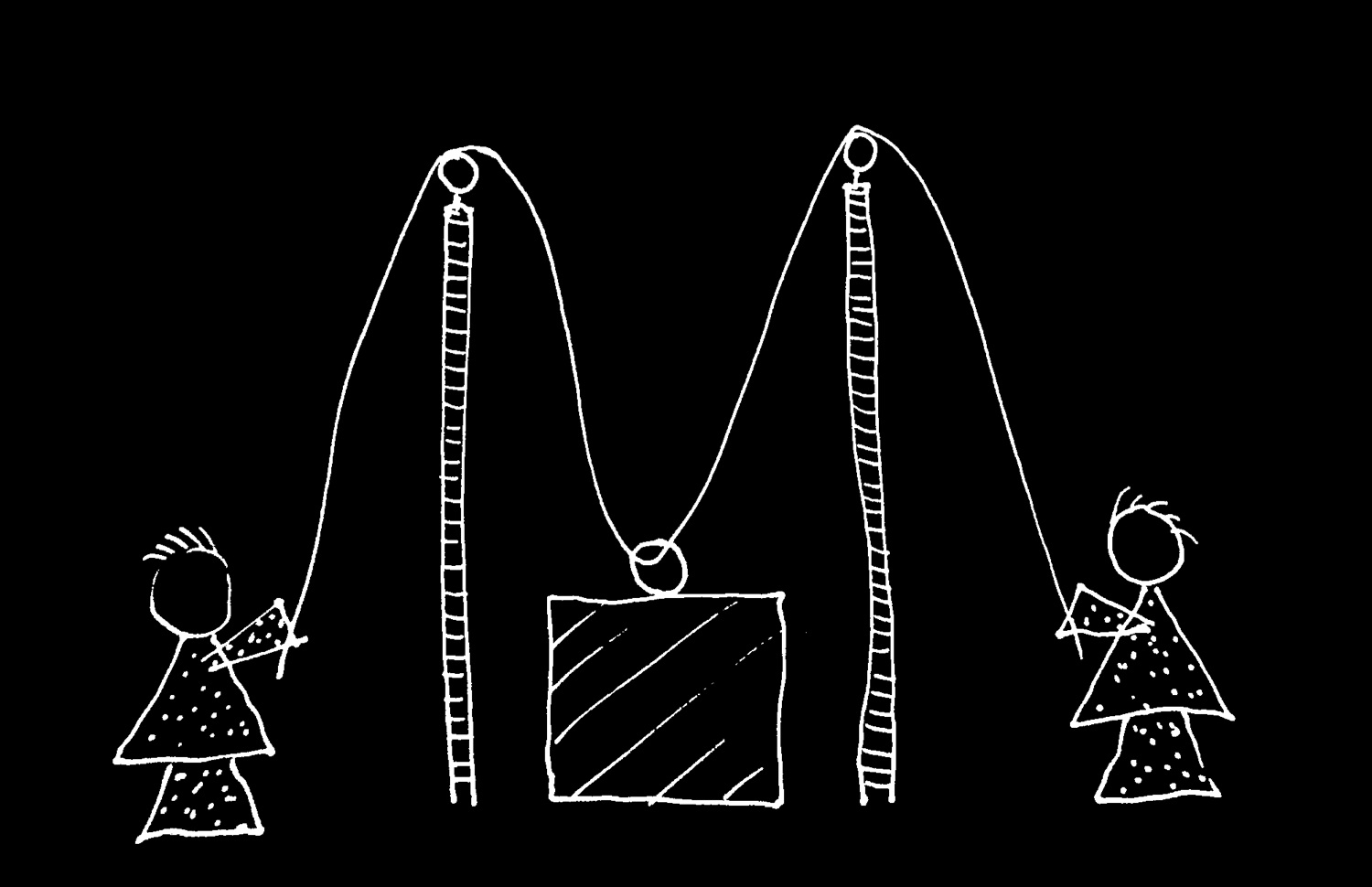

Are Ayesha and Beatrice

acting together?

Is Ayesha and Beatrice’s

lifting the block together

a joint action?

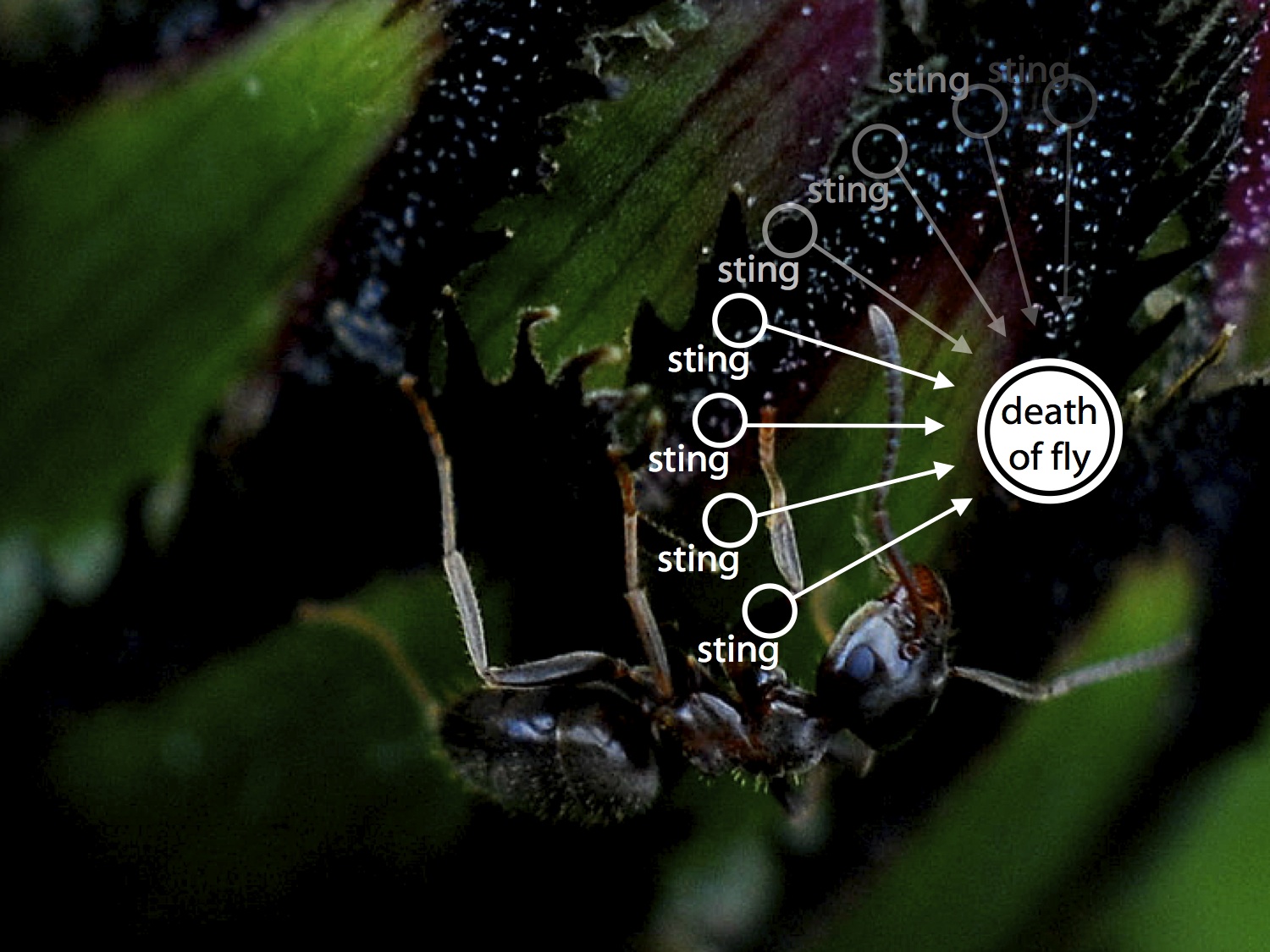

collective vs distributive

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

Give another

collective-distributive

contrast pair.

The tiny drops fell from the bottle.

- distributive

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers.

- collective

Their thoughtless actions soaked Zach’s trousers. [causal]

- ambiguous (really!)

Claim:

When collective, they act together.

The tiny drops soaked Zach’s trousers together.

The three legs of the tripod support the camera together.

Ayesha and Beatrice lifted the block together.

- In each case there is a collective interpretation.

- The collective interpretation is what makes ‘together’ appropriate.

- It is the same sense of ‘together’ in each case.

- The truth of the collective interpretation of (c) does not depend on there being any intentional joint action.

- So two or more people can do something together without thereby performing a joint action

We each intend that we, you and I, cycle to school together.