Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

The Problem of Joint Action

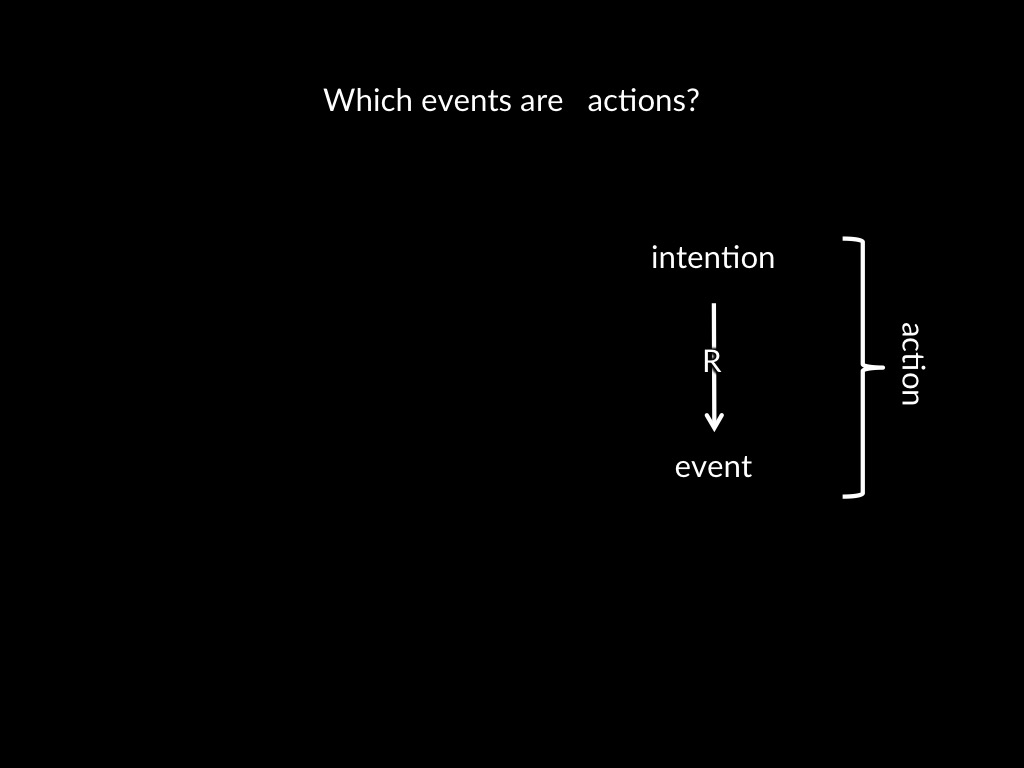

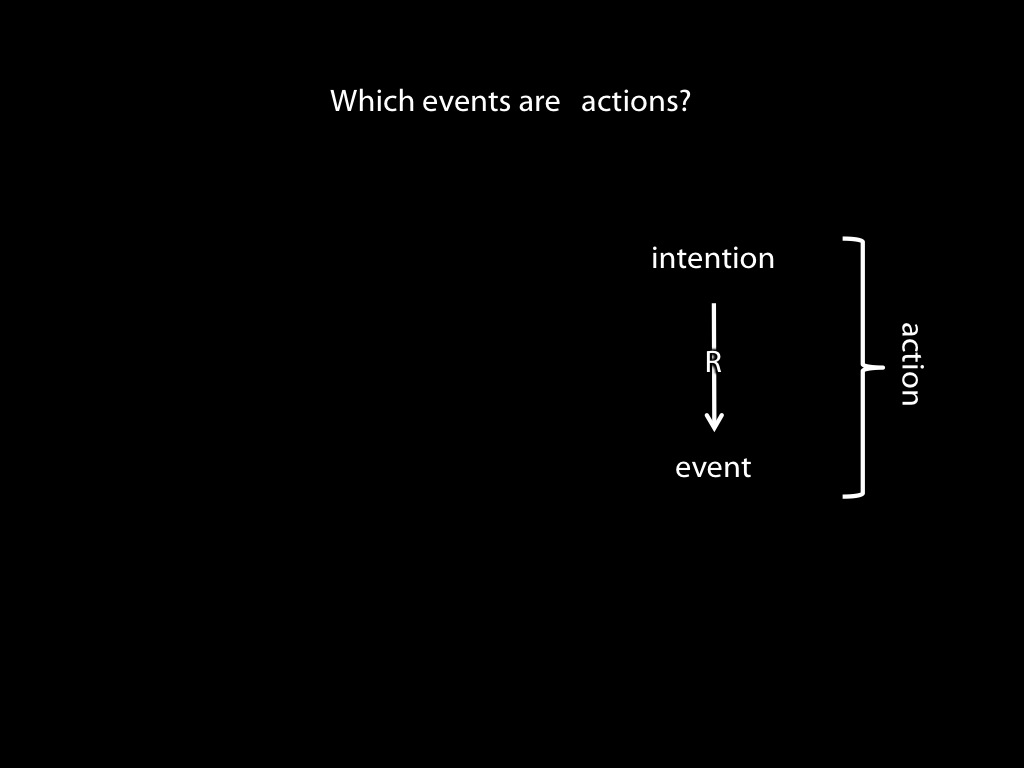

‘What events in the life of a person reveal agency; what are his [sic] deeds and his doings in contrast to mere happenings in his history; what is the mark that distinguishes his actions?’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 43)

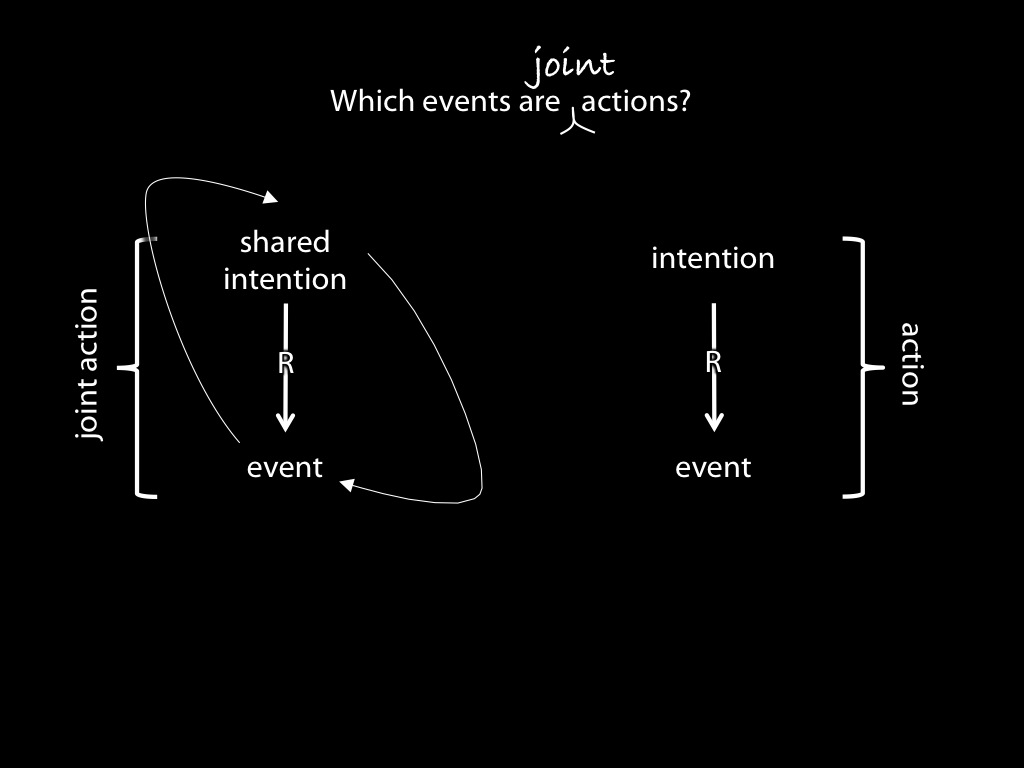

‘we have one correct answer to our problem: a man is the agent of an act if what he does can be described under an aspect that makes it intentional.’

(Davidson, 1971, p. 46)

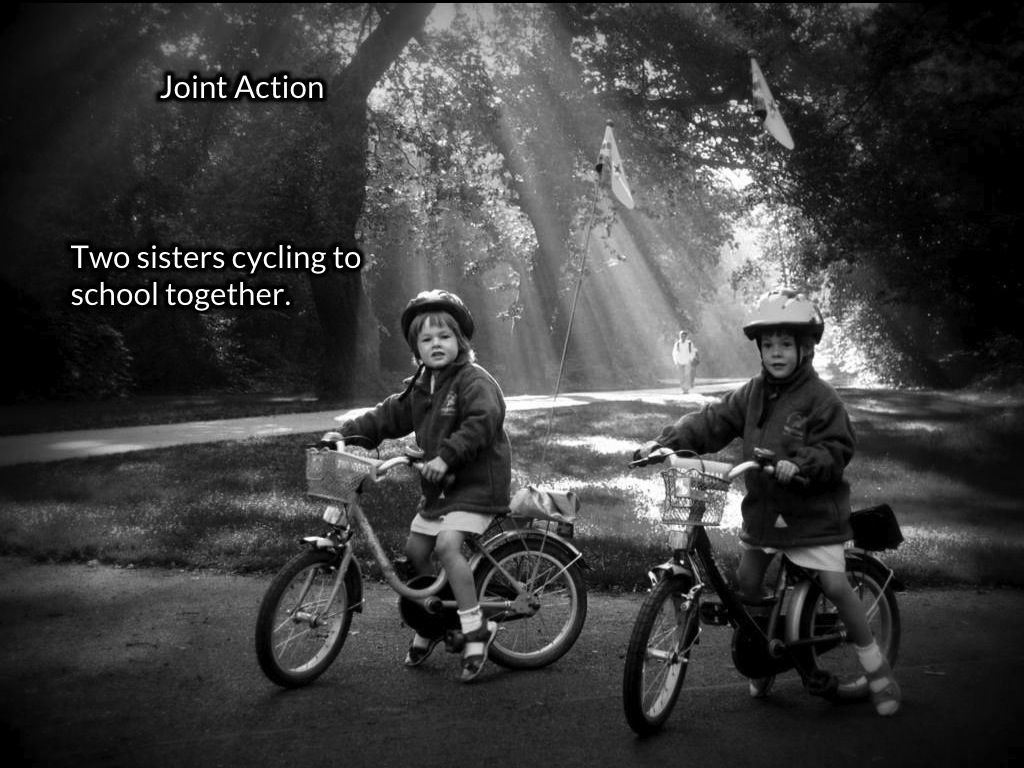

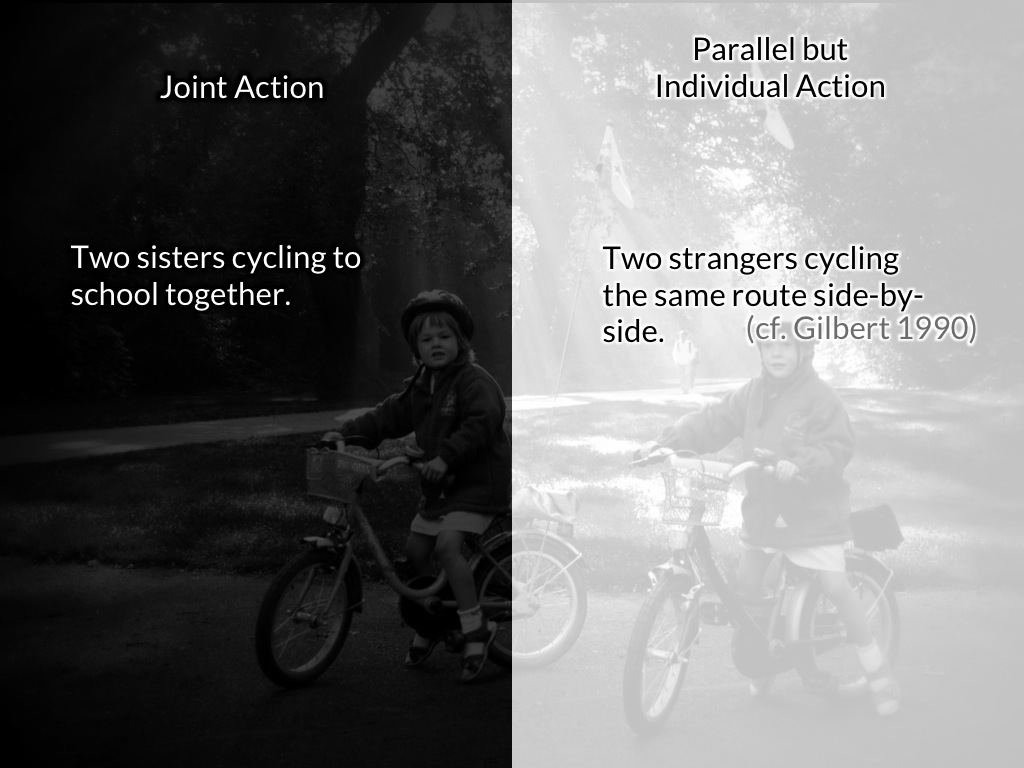

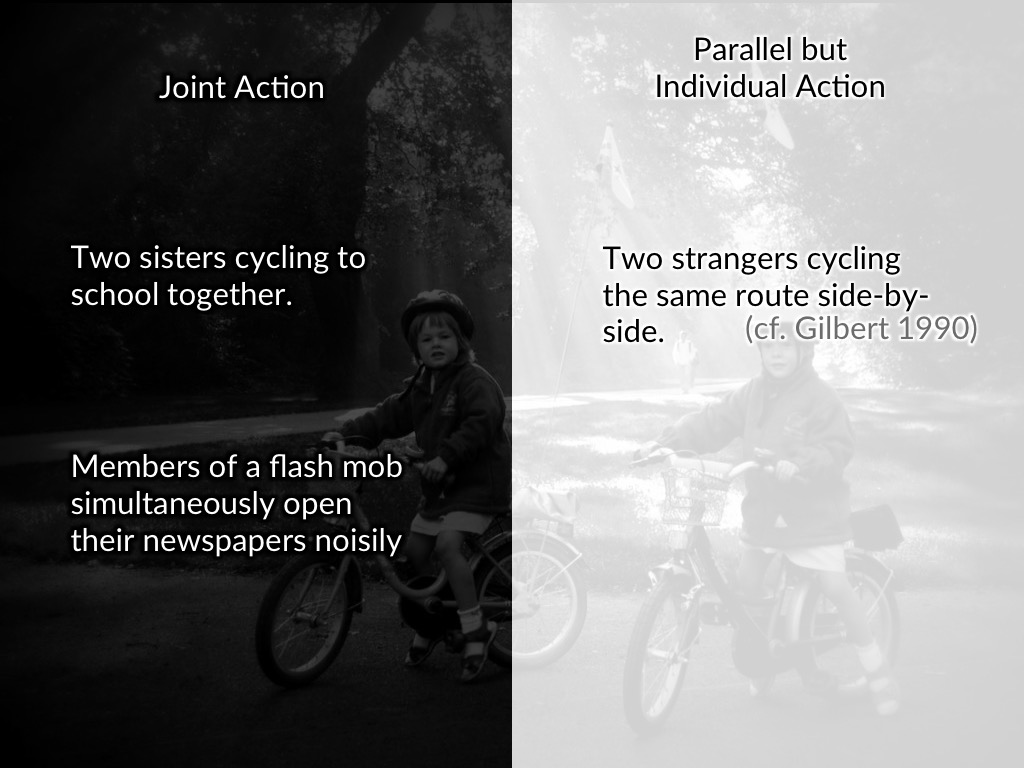

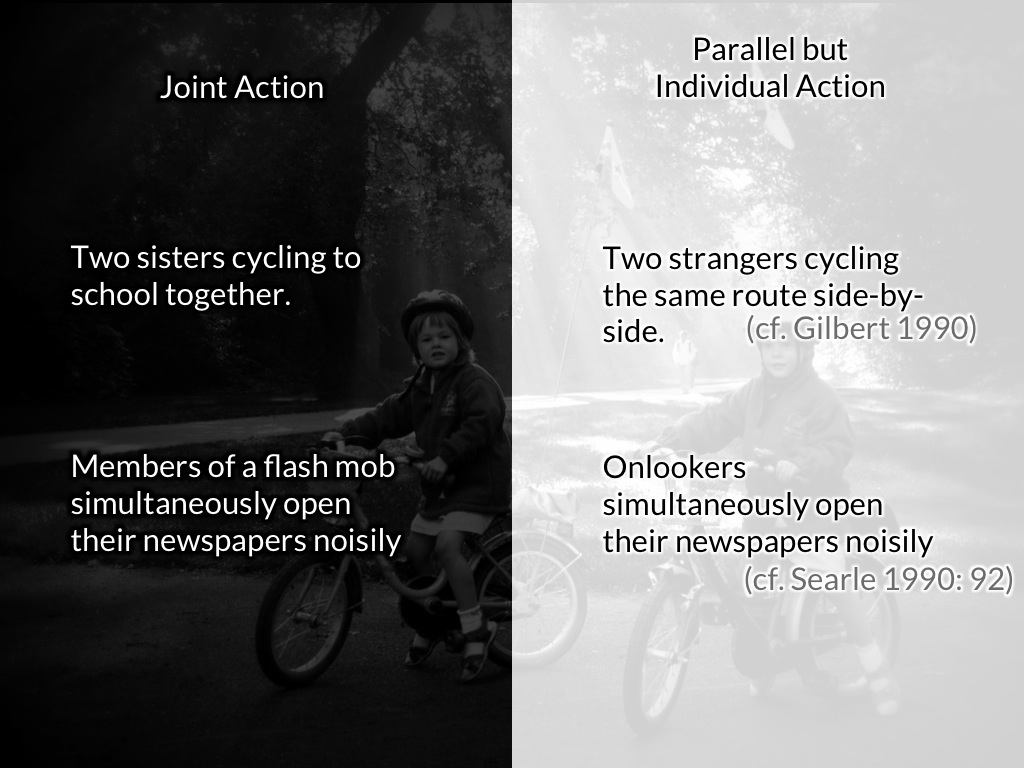

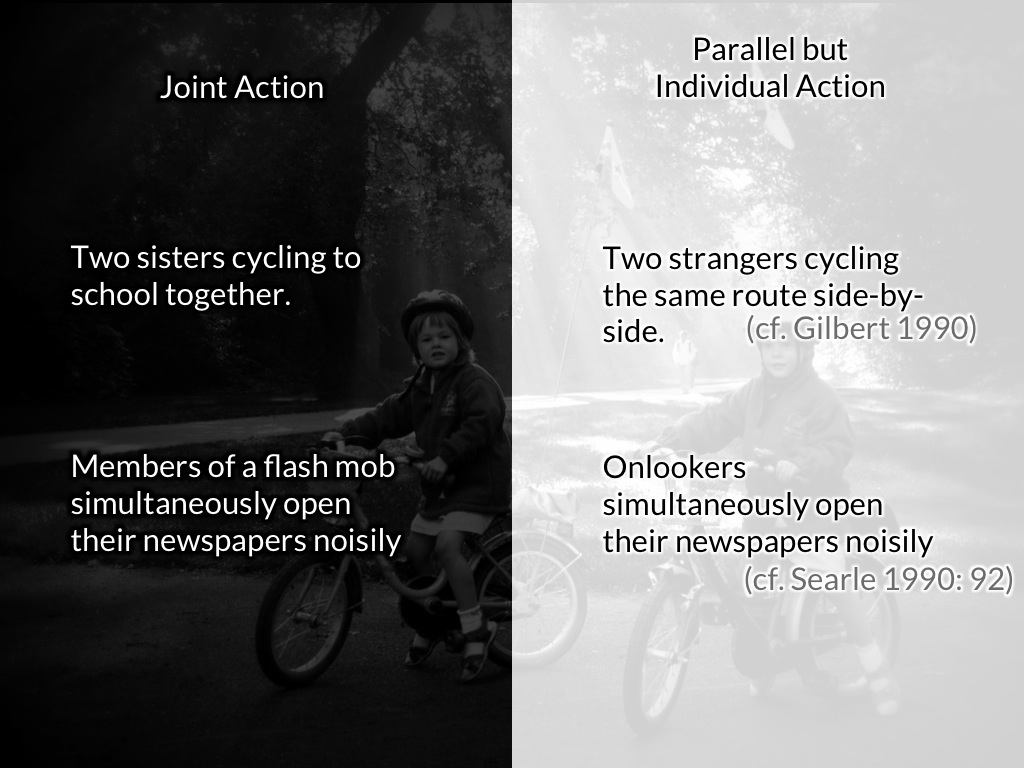

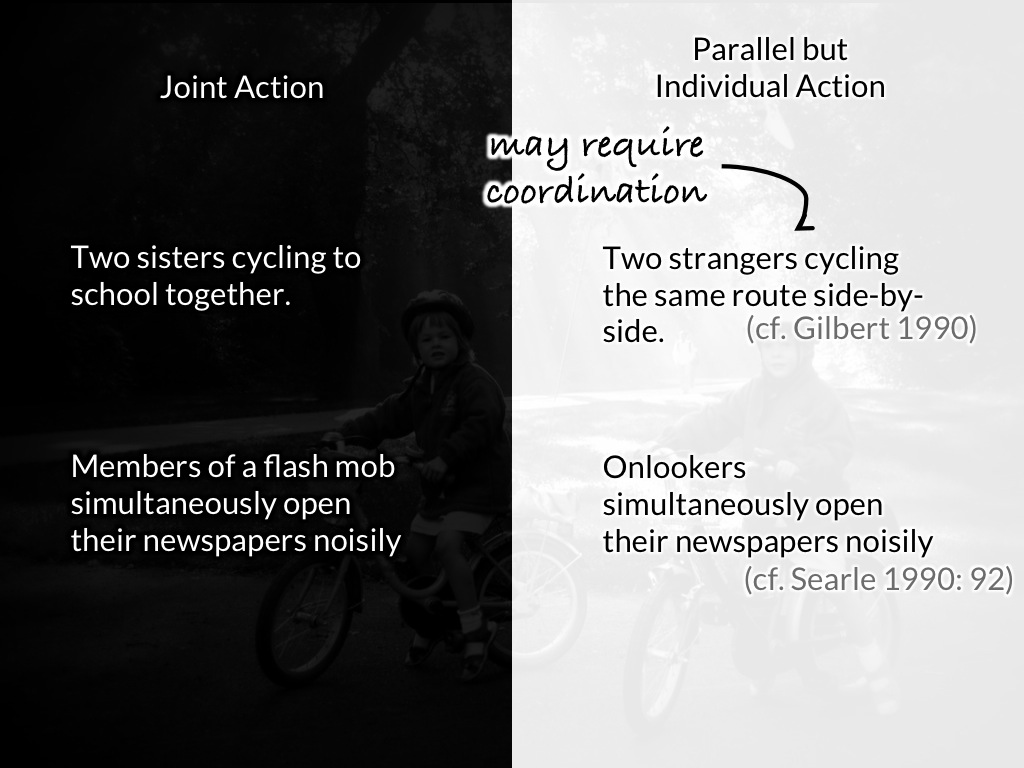

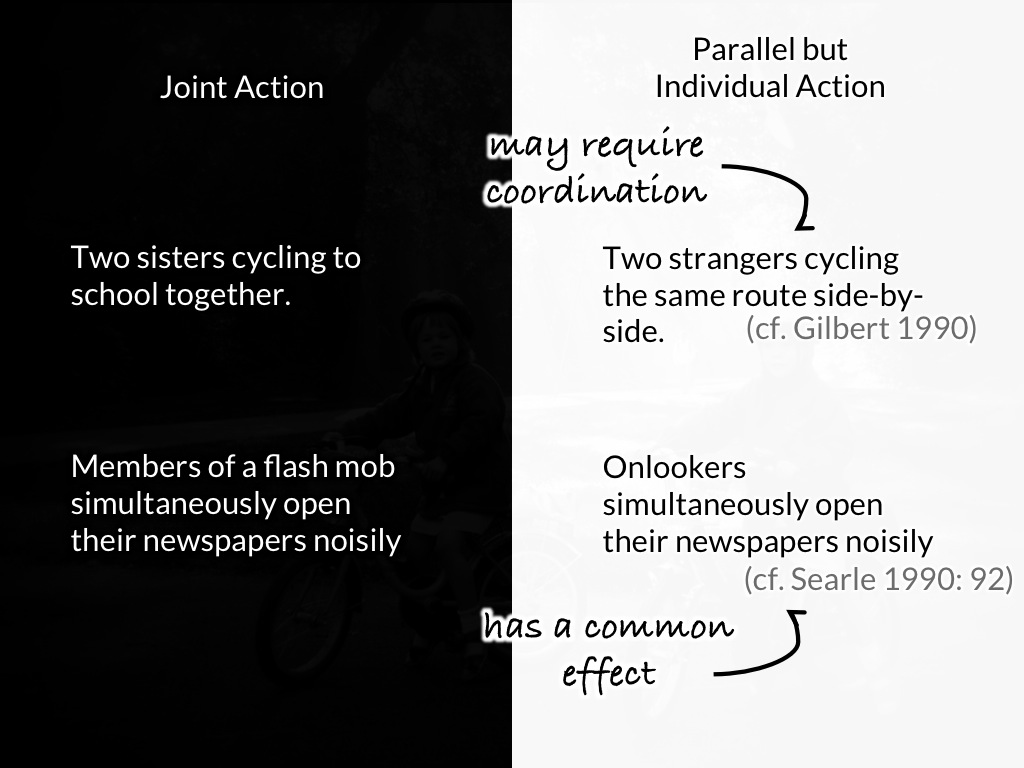

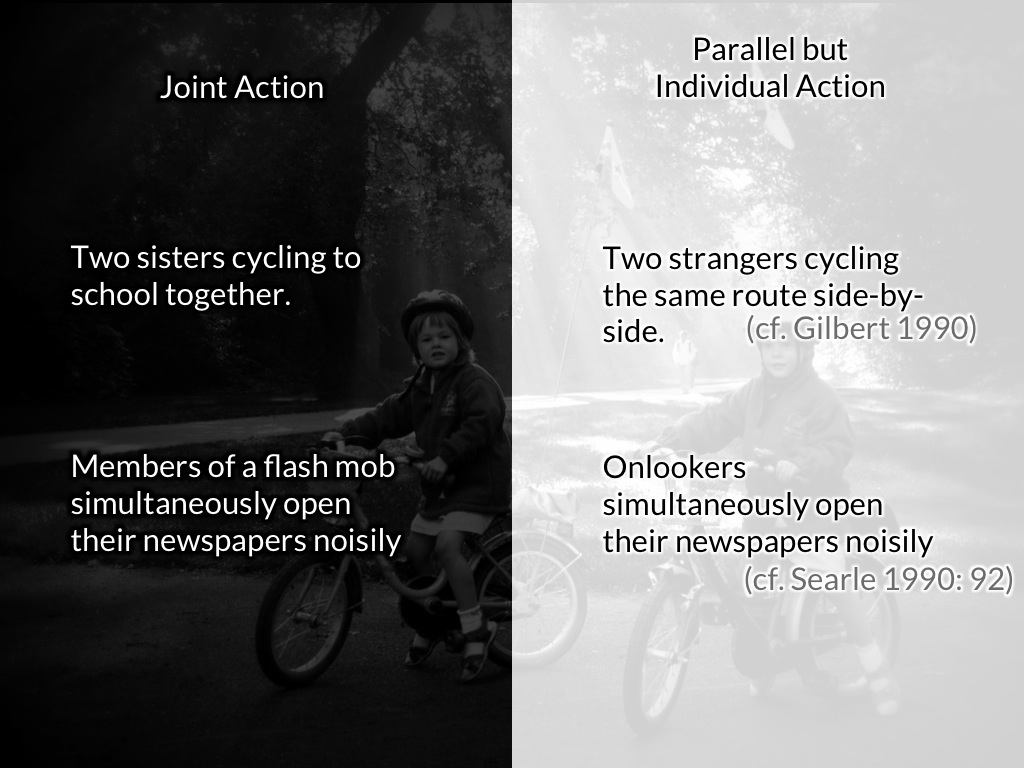

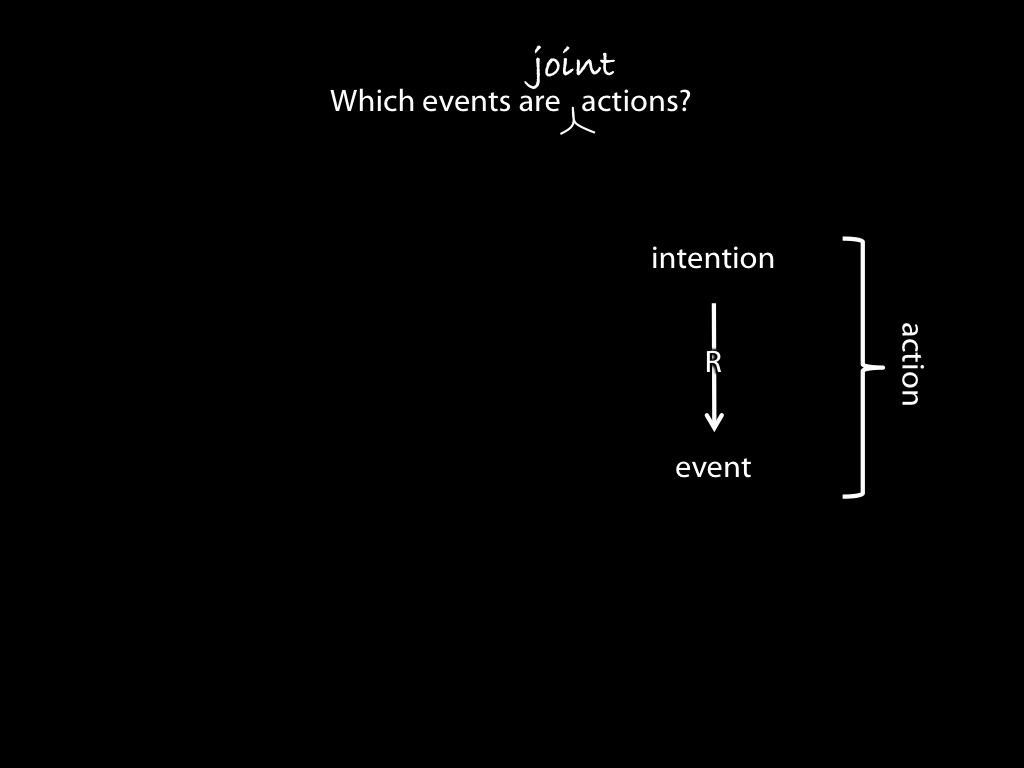

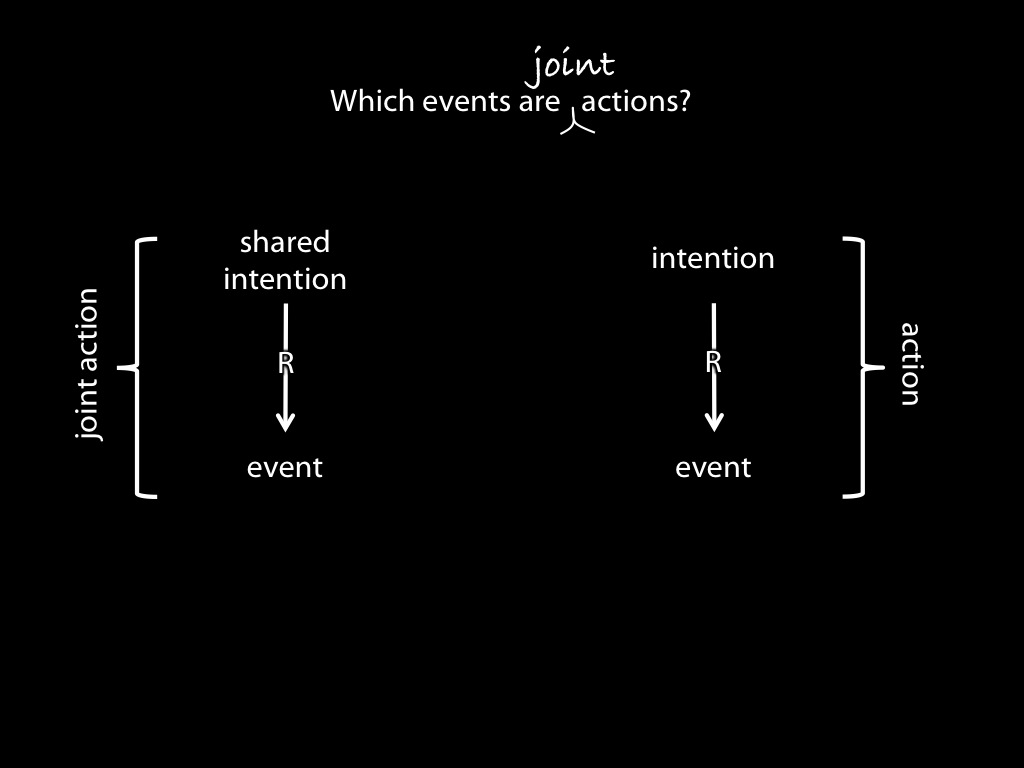

[joint action] What distinguishes doing something jointly with another person from acting in parallel with them but merely side by side?

Give another contrast pair.

Question

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Theoretical framework for psychology and formal models.

‘discover the nature of social groups in general’ (Gilbert, 1990, p. 2)

understand the conceptual, metaphysical and normative aspects of basic forms of sociality (Bratman, 2014, p. 3).

Question

What distinguishes joint actions from parallel but merely individual actions?

Requirement

Any account of shared agency must draw a line between joint actions and parallel but merely individual actions.

Aim

Theoretical framework for psychology and formal models.

short essay question:

Why, if at all, do we need a theory of shared intention?

(Will be a while before this question makes sense.)

plan d’attaque

premise: Shared intention can only be understood as the solution to a problem.

1. What is the Problem of Joint Action? ✓

2. Can we solve the Problem without shared intention? ✓

3. If we do need shared intention, what is the best account available? ✓

shared intention

‘A first step is to say that what distinguishes’ the sisters cycling together from the strangers cycling side by side is that the sisters share an intention to cycle together ... but the strangers do not.

‘This does not, however, get us very far; for we do not yet know what a shared intention is’

Bratman, 2009 p. 152

‘I take a collective action to involve a collective [shared] intention.’

(Gilbert 2006, p. 5)

‘The sine qua non of collaborative action is a joint goal [shared intention] and a joint commitment’

(Tomasello 2008, p. 181)

‘the key property of joint action lies in its internal component [...] in the participants’ having a “collective” or “shared” intention.’

(Alonso 2009, pp. 444-5)

‘Shared intentionality is the foundation upon which joint action is built.’

(Carpenter 2009, p. 381)

?

shared intention

‘shared’ 1 : Ayesha and her best friend have the same haircut

-> the Simple Theory (not what they have in mind)

‘shared’ 2 : Ayesha and her brother share a mother

-> plural subject account (Schmid, Helm)

e.g. our volume, yours and mine, is approx 130 litres.

cf. our intention, yours and mine, is that we paint the house.

‘shared’ 3: The group shares a wheelbarrow

-> aggregate (or ‘group’) agent (Pettit, Gold & Sugden)

?

shared intention

- not shared; not intention

| SHARED INTENTION | yes | no |

| Does it entail commitment? | Gilbert (2009) | Kopec & Miller (2018) |

| entails knowing you have it? | (many) | Roy & Schwenkenbecher (2021) |

| leads to cooperative actions? | Bratman (2014) | Salomone-Sehr (2022) |

| can only be formed in one way? | Gold & Sugden (2007) | (many) |

| entails believing others will do their parts? | Tuomela (2005) | Ludwig (2015) |

| multiple forms exist? | Pacherie (2013) | Bratman (2014) |

‘A first step is to say that what distinguishes’ the sisters cycling together from the strangers cycling side by side is that the sisters share an intention to cycle together ... but the strangers do not.

‘This does not, however, get us very far; for we do not yet know what a shared intention is’

Bratman, 2009 p. 152

short essay question:

Why, if at all, do we need a theory of shared intention?

(Will be a while before this question makes sense.)

plan d’attaque

premise: Shared intention can only be understood as the solution to a problem.

1. What is the Problem of Joint Action? ✓

2. Can we solve the Problem without shared intention? ✓

3. If we do need shared intention, what is the best account available? ✓