Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Expected Utility

decision theory

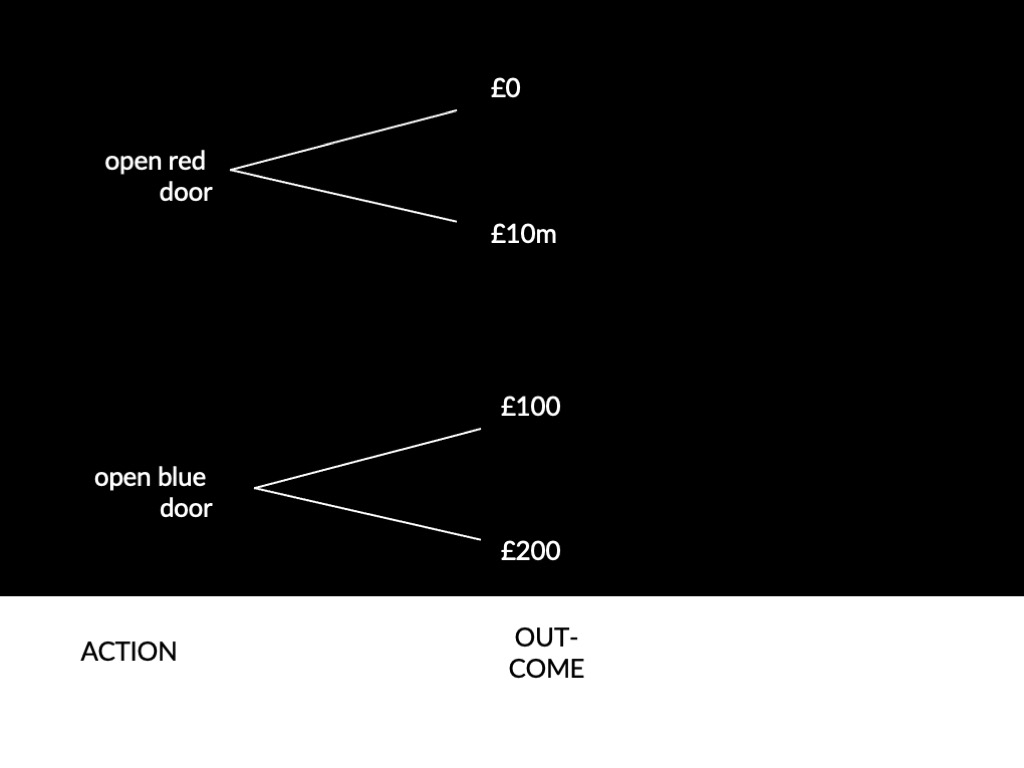

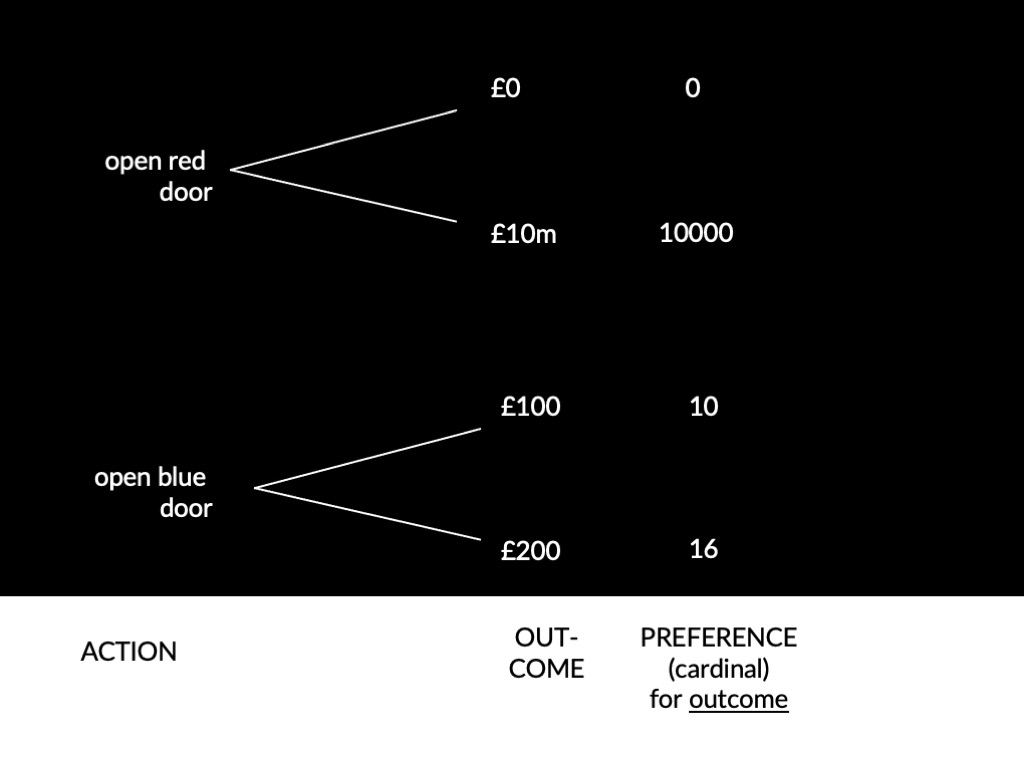

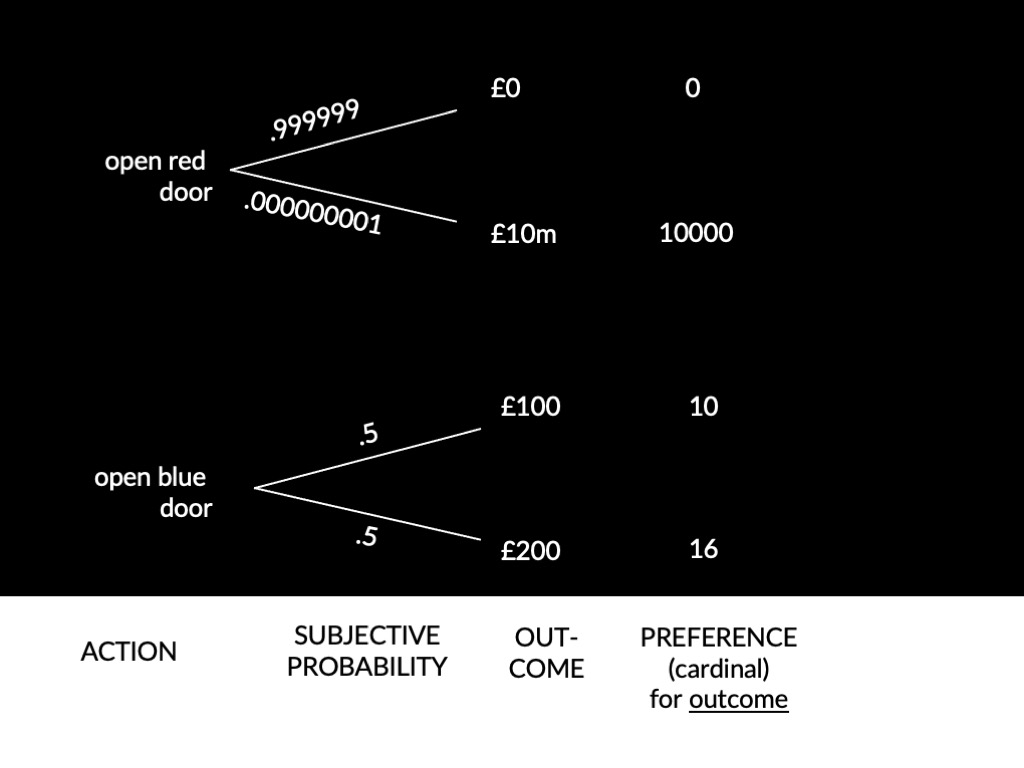

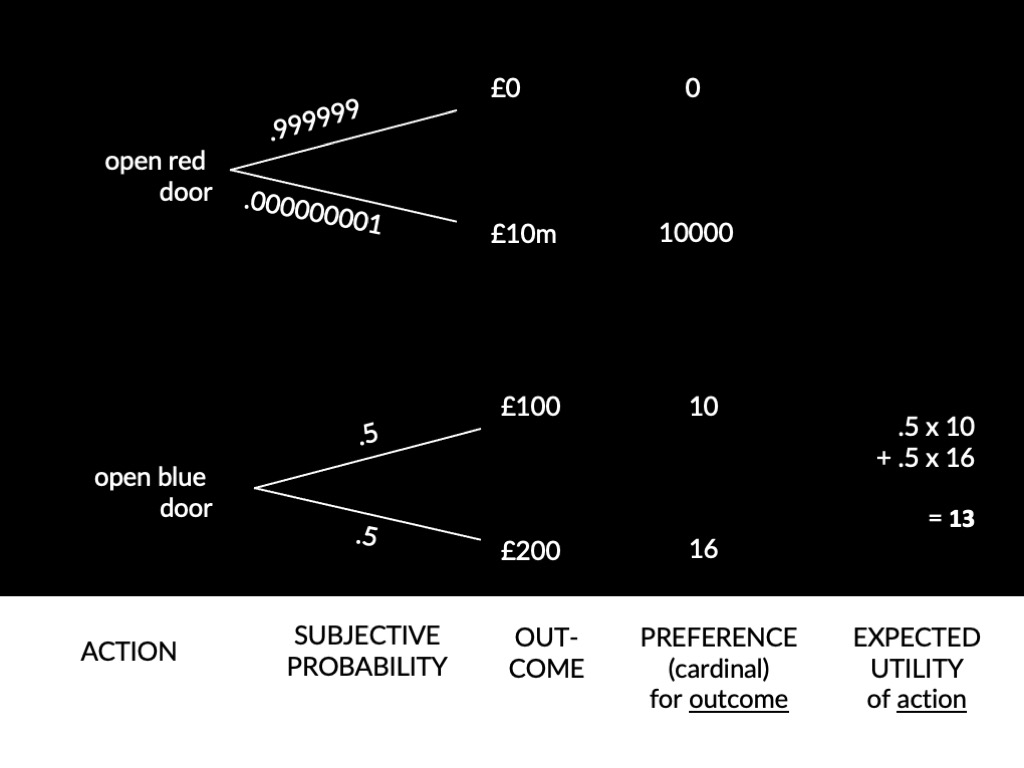

How do rational agents decide which of several available actions to perform?

Terminology

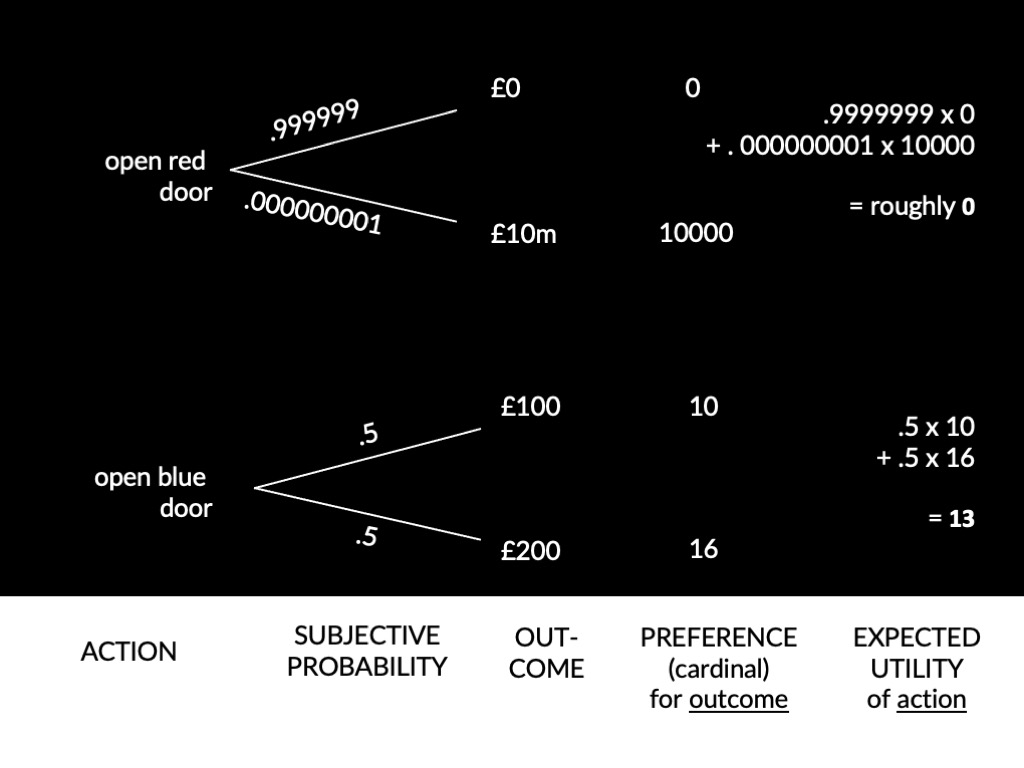

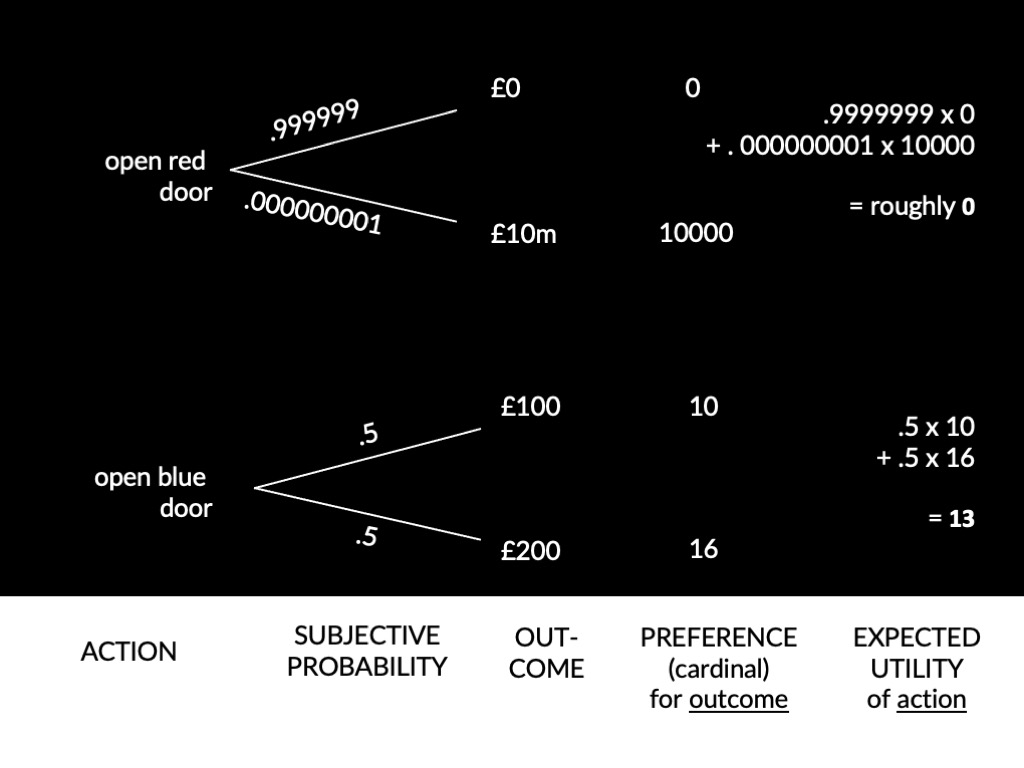

actions have outcomes

(Jeffrey: outcome = ‘consequence’)

which outcome an action causes depends on **conditions**

subjective probabilities attach to conditions.

preferences rank outcomes

expected utilities attach to actions.

(Jeffrey: expected utility = ‘estimated desirabilities’)

Jeffrey (1983)

so far: the representation

next step: the theory

This book has ‘a philosophical end: elucidation of the notions of subjective probability and subjective desirability or utility’

(Jeffrey, 1983, p. xi)

‘we [...] view

subjective values and probabilities

as interrelated constructs of decision theory’

(Davidson, 1974, p. 146)