Click here and press the right key for the next slide.

(This may not work on mobile or ipad. You can try using chrome or firefox, but even that may fail. Sorry.)

also ...

Press the left key to go backwards (or swipe right)

Press n to toggle whether notes are shown (or add '?notes' to the url before the #)

Press m or double tap to slide thumbnails (menu)

Press ? at any time to show the keyboard shortcuts

Are Objections to Decision Theory also Objections to the Dual Process Theory of Action?

overview

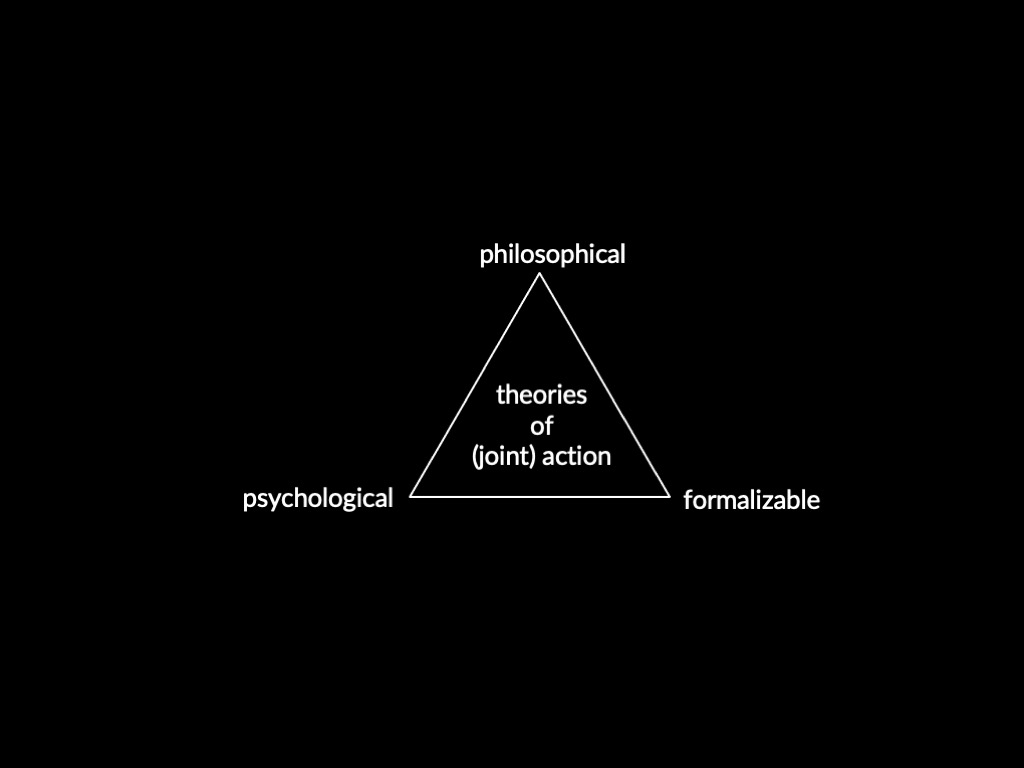

Problem: how to characterize the goal-directed process such that we can generate action predictions.

Candidate solution: the goal-directed process is the computation of expected utility.

Objection: the goal-directed process does not compute expected utiltiy.

Illustration: Ellsberg Paradox

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

What are beliefs? And what are desires?

If you replace them with subjective probabilities and preferences, this question is easy to answer: they are constructs of decision theory.

How do beliefs and desires determine actions (or intentions)?

The agents’ subjective probabilities and preferences determine the expected utilities of various actions she could take.

The agent selects the action with most expected utility.

habitual process

Action occurs in the presence of Stimulus.

Outcome follows action

Agent is rewarded

Stimulus-Action Link is strengthened due to reward

Given Stimulus, will Action occur? It depends on the strength of the Stimulus-Action Link.

‘goal-directed’ process

Action leads to Outcome.

Belief in Action-Outcome link is strengthened.

Agent has a Desire for the Outcome

Will Action occur? It depends on the Belief in the Action-Outcome Link and Agent’s Desire.

problem:

Agents who make certain choices do not have subjective probabilities or preferences at all.

And many agents do make such choices (the Ellsberg Paradox illustrates; Jia, Furlong, Gao, Santos, & Levy, 2020).

consequence:

To characterise goal-directed processes in terms of decision theory is to deny that goal-directed process occur in agents with aversion to ambiguity (and other conditions).

What should we do?

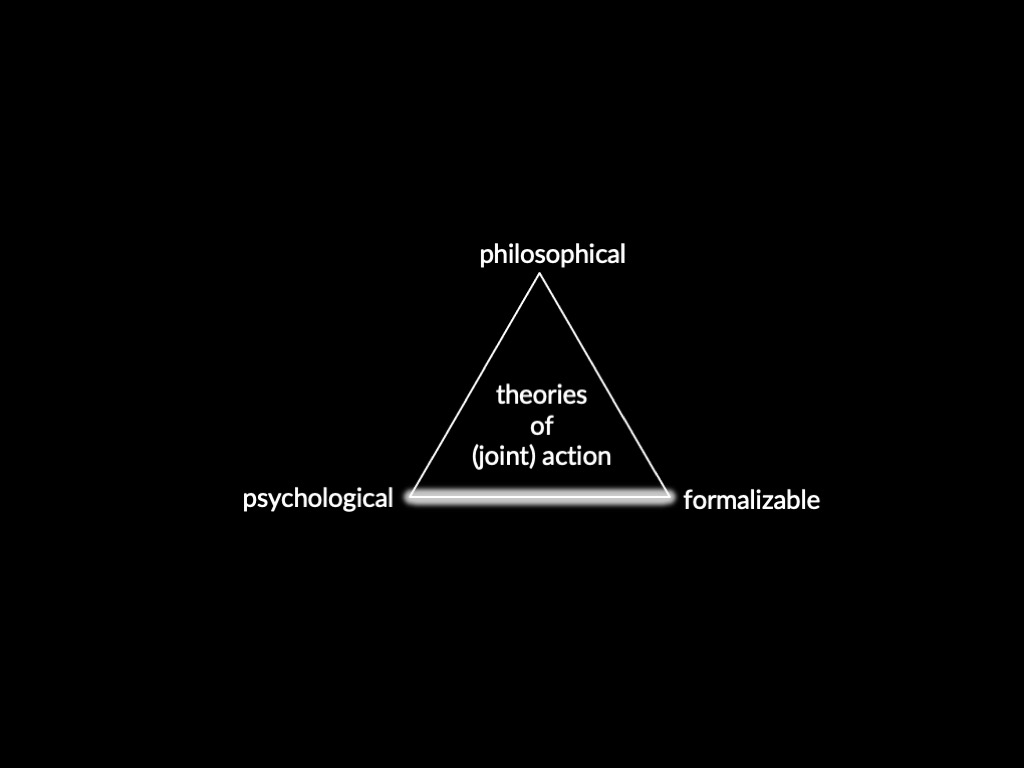

option 1: find a way to hold on to decision theory despite the objections

option 2: find an alternative formalization

(cumulative prospect theory Tversky & Kahneman, 1992?)

option 3: find an informal way to characterise these processes